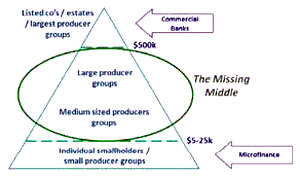

A new approach to upscaling agricultural finance for the missing middle.

New risk-profiling approaches offer the promise of helping the “missing middle”: farmers who are too small to attract loans or be of interest to commercial banks, and too large to benefit from microfinance institutes.

Banks interested in supporting agriculture all aim at the same group of large, well established farms with a good track record, credibility and collateral. Transaction costs play a large role here: it is much more profitable to build long-term relationships with big farms, which need big loans, than with many clients who need smaller loans. Regardless of the size of the loan, a bank has to do the same amount of work in assessing the risks involved and providing financial services. The marketing process, the due diligence, the financial transactions and the monitoring process, all take the same time, whether it is for a loan of US$ 10,000 or one of one million dollars. In addition, bigger farms tend to be better managed; they can provide more information about the work they do and the risks they take. It is not surprising that banks prefer to work with them. At the same time, there are now microfinance institutions (MFIs) in many parts of the world.

They have been able to bridge this information gap by setting up social structures (often groups of entrepreneurs) which are then responsible for the financial behaviour of individual members. This significantly reduces the information and monitoring costs. MFIs have also pioneered the way of dealing with collateral by accepting “soft” collateral like contracts, links with other parties in the value chain, technical assistance, or insurance. MFIs are often involved in creating soft collateral themselves, helping their clients improve their business and thus securing their lending. This model has dramatically changed the opportunities for many of those at the bottom of the pyramid. However, this approach still follows a “relationship banking” model, which is time-consuming and expensive. Though the model is replicable, it is difficult to scale it up to reach those who are part of the “missing middle”.

Bridging the gap

Traditionally, banks look at two C’s: collateral and capital. Without one of these, they are not likely to provide loans. More progressive banks will also take into account two more C’s: crops and contracts, which can function as soft collateral for loans. However, those four C’s only look at the results of previous investments, without giving a full idea of the possibilities of success in the future. Withholding loans to farmers who can’t show one of these four C’s pushes them into a vicious circle: without investments, they can’t improve their business and they will never get the sufficient collateral, capital, contracts or crops needed to attract investments and improve their business.

Farmers can escape this vicious circle if banks are willing to take other kinds of collateral, or look at information which can show success in the future. Among this, a few more C’s can be included:

- Capacity and character: what is the farmer’s capacity to manage her farm? Does she have an entrepreneurial spirit? Does she receive technical assistance?

- Competitiveness: does the farmer know her market and is she able to adapt product, quantities and qualities to market demands?

- Context and chain: how is the farmer embedded in the value chain? Does she have long-term contracts with the same suppliers and processors or traders?

- Certification: is the farmer certified, and does this enhance good agricultural and management practices? Does the certification scheme generate a price premium?

- Cash flow: what are the future cash flows? Does the farmer have a financial management system?

- Credibility: what is the farmer’s financial track record?

By scoring a farmer on the basis of these additional factors, banks can get a more comprehensive insight, and this can serve as the necessary input for their own due diligence process.

Putting it into practice

Systematic risks

In agricultural finance, banks often consider the systematic risks to be the most important ones. These are the risks that are inherent to a whole sector and/or a whole region, such as weather risks, biological risks or price risks. If drought, flooding or a pest outbreak hits a region, it will affect most of the farmers. If prices are going down, all the farmers will be paid less for their products. One of the core strategies of a bank is to diversify their investments, in order to reduce these risks. (This is another reason why banks prefer to stay out of agricultural finance, as the sector is replete with systematic risks.)

Due to their nature, systematic risks are difficult for individual farmers to manage. However, there are risk management strategies which can – at least – mitigate against their effect. Drought can be managed or mitigated by crop diversification (not all crops are equally sensitive), irrigation or insurance. Price risks can be managed by storage facilities (helping farmers wait for better prices). Putting these strategies into practice is a clear indicator of good management and reduces systematic risk.

ForeFinance is a company that makes profiles of farmers based on the C’s mentioned above. This assessment is done at a group level, for several reasons. First, working with co-operatives (or other groups) can be more cost effective. Moreover, a group provides some of the essential “soft” collateral: adequate governance and management structures, links with the value chain, certification, financial management or links with technical assistance. ForeFinance has started business in Kenya, and aims to roll out this concept throughout Africa, Latin America and Asia.

The profiling process starts with a request from a group. A third party audit is conducted, which generates a profile of the group. This profile is stored in a database, which is accessible to banks. On the basis of this profile and their own due diligence, a bank can decide to provide a loan which, together with the repayment details, is recorded in the database. The link with those who provide technical assistance is very important, as they often have extensive experience with the farmer and can provide additional information. When a profile is made, it also generates insights of what has to be done to make the farmer(s) more bankable. This information can be delivered to those providing training or extension.

The relevant importance of these indicators varies between sectors and regions. Among Kenyan coffee farmers, for example, governance and credibility are two very important factors, as coffee co-operatives have a history of bad governance and debt forgiveness. The variables are weighted before they are put into a model which gives a producer group a credit rating from A to D. This serves as an input for the bank’s due diligence, which then allows the bank to concentrate on analysing systematic risks (see box).

Pieces of the puzzle

Certification schemes (in for example coffee, tea and cacao) have helped make whole sectors more transparent, efficient and sustainable, and have brought clear benefits to farmers. Although our work does not intend to be a certification scheme, we think it can lead to the same dynamics and benefits.

Of course, our methodology is only a small part of the puzzle which has to be in place to overcome the financing gap. Change has to come from different sources. Governments can help create a stable context for agriculture. They are responsible for providing the necessary infrastructure (roads, telecommunications) and can regulate and prevent market distortions. Non-governmental organisations have played, and continue to play, an important role in training and extension activities.

However, the major drivers of change have to come from the agricultural and financial sectors themselves. While the model can be a driver in making farmers more “bankable”, it is clear that banks have to become more farmer-friendly. They need encouragement and support in this. Encouragement can come from a first-loss structure, which can compensate banks in case of defaults. A fund to subsidise the initial profiling of farmers also seems necessary. Both schemes are currently being set up by the independent consultancy firm Agri Finance Program Management & Consultancy. These schemes are expected to help this model spread, helping more and more farmers get access to credit – and with it, get higher yields.

Text: Jaime ter Linden

Jaime ter Linden is program manager at ForeFinance. He has worked in the financial sector for many years as an analyst and portfolio manager.

E-mail: jaime.ter.linden@forefinance.nl