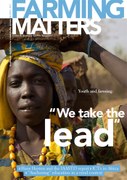

Favourite dishes are a matter of taste, and each person’s taste differs. Young people’s tastes are often thought to be for fast and easy food. But there is an alternative trend: many young people want good food on their plates.

In the United States, an energetic and positive youth movement has been pioneering a “delicious revolution”. Amongst American students there is a sense of rage about the purely economic and

non-sustainable choices provided by the food industry and by multinational companies like Monsanto. In 2000 a group of students at Yale University heard that pesticides were being used on the food that they were being served on campus, and they opened discussions on food procurement.

“Slow Food on Campus” has now spread to many colleges and universities and is reportedly having a real impact on food consumption across the U.S. Activities include “boycotts” of meals not including fair-trade, local produce, “buy-cotts” which offer opportunities to buy local products, “eat-ins” where local produce is shared on campus, and also “cookouts”, during which students provide meals to local farmers to thank them.

British students are also getting more active around food, trying chiefly to maintain quality through hard times. Decent, well-sourced food is particularly a high priority for hungry students descending into debt. Slow Food activism also resonates with a renaissance in foraging, bush crafts, home-brewing and baking. Students’ appetites for healthier and locally-sourced food is also shown in the success of the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) co-operative shop in London that sells competitively priced, organic and fair-trade foods. Such enterprising activities directly challenge the monopolies of the enormous multinationals that dominate institutional catering.

Worldwide concerns

Although those behind these different efforts may not know each other, and may not co-ordinate their activities, they all respond to similar interests and concerns: they want to know where their food comes from, how it is produced, and by whom. Young people play a key role in schools and universities, but also – increasingly – as part of international movements like Slow Food and several others.

Slow Food was founded to promote the gastronomic heritage of different places. For Carlo Petrini, its founder, young people will play a key role, as the generation who will reunite mankind with the earth. And young people are also taking key roles within the movement itself. Since 2008, Slow Food’s vice president is John Kariuki, a 23-year-old farmer’s son from Kenya.

Last October, at the latest Slow Food meeting known as “Terra Madre” (held every two years in Turin), John Kariuki showed that young people from his own country, and elsewhere in Africa, are equally concerned about the global food industry and its impact on food habits and consumption. In Africa, young people are also starting initiatives and projects to offer alternative ways to relate with food. Mr Kariuki highlighted the growth of school gardens in Kenya and described the importance of teaching children about food and farming. Many children who experience school gardens go back and teach their entire households and communities about local foods and sustainable farming.

Gardens and schools

These experiences from Kenya have inspired a Slow Food project called “A Thousand Gardens in Africa”, which is promoting gardens as platforms for education. School kitchen gardens are being developed in order to exchange knowledge about local produce, share seeds, preserve agrobiodiversity, safeguard local recipes and learn how to transform food through preservation, storage and cooking. There is also an emphasis on intergenerational learning, such as bringing in elders to tell children stories and transmit their time-honoured knowledge of the land and growing food. School Gardens have already been set up in 17 countries, including Congo, Guinea Bissau and Madagascar.

In Uganda, Slow Food co-ordinator Eddie Mukiibi (23) stresses the importance of food and taste in education: “If a person doesn’t know how to eat food, he won’t grow food”. As part of the project he runs, “Developing Innovations in School Cultivation” (DISC), children learn how to cook and prepare traditional foods, and how to grow local crops like amaranth, aubergine, sukumawiki and maize from local seeds. He works with each school, helping them to plan, construct and know how to care for their garden, looking for the best ways to deal with local climatic challenges such as drought and erosion. Produce from the gardens is used in the school meals, or sold at local markets. Some schools transform produce into preserves and jams.

Food and farming

Food and farming do not formally feature in most educational curricula, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. In many countries farming has been used as a form of punishment in schools, and becoming a farmer perceived as the last option, after one has failed to get an education or a job. So school gardening projects in Africa often meet with initial resistance from parents and teachers who think that it will detract from children’s studies. But children need to know how to survive economic downturns, by learning the right skills, knowledge and attitudes for becoming autonomous and self-sufficient. It is important not only to raise awareness about the value of gardening, but also to raise its prestige and highlight the enjoyment and even therapeutic benefit that can be gained from interacting with plants.

In the end, these youth activities will propel students into a new realm of activism around food and mobilise people to go back to nature, communal farming and growing food. Terra Madre 2010 was a testament to the fact that young people are our greatest hope for creating a new, sustainable agrifood system. Worldwide, young people are recognising the connections between good food, good health and flourishing communities. Food education is an education for life; learning to grow one’s own food and cook, the ultimate declaration of independence.

Text: Petra Bakewell-Stone

Petra Bakewell-Stone is an independent consultant based in the U.K. and Tanzania.