Aiming to increase the area covered by forests, programmes like the Green India Mission are looking for the necessary funds and resources to help them reach the objective of reforesting millions of hectares. Yet money is not the only difficulty. For who owns these new forests? And who benefits from them? Setting up co-operative forests has many advantages, but they can suffer from an incomplete legal framework.

Amidst a dense canopy of teak trees, a beaming Dina Nath Singh lists the many benefits coming from the 265 hectares of forested area that he has helped establish. Protected and replanted since 1997, the manmade forest in the village of Jaitpur Kachhya, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, is an oasis in an otherwise denuded area. While lopping and collecting litter from the forested area have been tangible benefits for the villagers, Mr Singh is more interested in talking about the intangible benefits that the community draws from the greenery. “The fact that many like me lead a healthy life may have to do with the fresh air we receive as a bargain”, he says. Being the founding chairman of the local Primary Farm Forestry Co-operative Society, he has a deep personal commitment towards forests and the environment.

Located about 50 km from the district town of Sagar, this forest co-operative has been effective in regenerating and conserving trees on public (government-owned) land. And as one travels some 10 km further from Jaitpur and approaches Dungariya, the forested hilltop can hardly be missed. An area of 212 hectares stands tall, covered with a wide variety of trees. According to the co-operative secretary, Rajneesh Mishra, “the area only needed protection for the root stock to regenerate and that is what we have done”. As a consequence, all along the periphery of the slopes the water levels in the village wells have shown marked improvement.

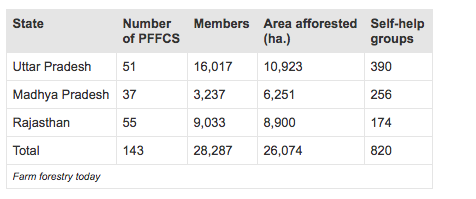

More than 4,800 hectares have been brought under tree cover through 29 co-operative societies in this district alone, showing that the rolling landscape is well suited for farm forests. And this total represents only one-fifth of the total number of Primary Farm Forestry Co-operative Societies (PFFCS) set up during the past 13 years by the Indian Farm Forestry Development Co-operative, or IFFDC. In total, IFFDC has helped 143 co-operative societies regenerate some 27,000 hectares of wastelands with trees in 13 districts in the states of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh.

A forestry initiative

The Indian Farm Forestry Co-operative (IFFDC) was established by the Indian Farmers Fertilizer Co-operative (IFFCO), one of the largest fertilizer co-operatives in the country. Since its inception, IFFDC has promoted farm forestry as a way of regenerating wastelands.

Their main interest was a model which would emphasise and help increase the role of the local community in managing and regenerating wastelands. The adoption of a co-operative model for forest farming was therefore the obvious choice, considering that:

- co-operatives have a legal status, and are not subordinate to the government;

- co-operative institutions are both economic and social entities, not mere charitable trusts or social clubs where members participate in social or recreational activities;

- the members are the owners: they have rights and responsibilities associated with electing directors and with giving general direction to their organisation;

- there is clear involvement of the members and this influences decision-making;

- the membership is diverse;

- their success depends on the efforts of their members, their mutual solidarity, their trust in their leaders and on their willingness to make sacrifices.

Another concern was how to achieve similar advantages to those provided by other models. Sacred groves are wooded areas that have existed for a very long time (in most cases dating from before the laws of the country were drafted). They are currently “socially protected” and are left undisturbed. In contrast, “joint forest management” programmes are agreements between a state’s Forest Department and local village forest committees, which give communities the right to extract non-timber forest products.

The co-operative farm forestry model is somewhere between the two: communities revere the forests, like sacred groves, yet also pursue economic activities based on the extraction of non-timber products and mature trees. Besides such products, the farm forests provide clean water and air, while the teak, eucalyptus, neem and bamboo farms also support animal biodiversity. But as an institutional innovation to generate and protect woodlots, farm forests still face a few unresolved issues.

Supplementing farm income

The first of these issues concerns the expected benefits. Although intangible benefits are acknowledged by some co-operative members, farm forestry on degraded lands has been promoted as a strategy for supplementing the limited income which farmers get from agriculture, integrating forestry into their regular farming practices. The way in which individual farming households are profiting varies as the schemes have been established on land under different forms of ownership.

Farmers in Rajasthan used panchayat land (common land at a village level); in Uttar Pradesh they used individually owned plots and in Madhya Pradesh state-government-owned lands. The commercialisation of different products (such as firewood) has meant that co-operative members are being paid for their efforts, and in some cases it is heard that the forestry co-operatives “have come to the rescue of the poor”.

In the districts of Sagar, Tikamgarh and Chhattarpur, in Madhya Pradesh, the total amounts which are reaching farmers are considerable: a total of 900,000 rupees, or US$ 20,000 for one year. The income from 6,251 hectares of afforested land has been shared equally between the 3,237 members. Yet, the net gain received by each member is not much, nor has it risen with time. This has led to brewing unrest amongst a large number of members, all of whom supposed that, once the woodlots were mature, they could share the benefits of the timber and that this would considerably increase their annual incomes.

Lack of clarity over ownership

Linked to these problems there is a second issue to deal with. The Forest Department and the forest co-operatives don’t always agree on who is the legal owner of mature trees. The Forest Department has been proclaiming ownership in some locations, and the current Forest Act prevents the co-operatives from selectively felling trees from non-forest lands. Similar uncertainties are also found within each co-operative, as seen in Jaswant Nagar, a village in the district of Tikamgarh. It has a 92-member Primary Farm Forestry Co-operative Society that has been allotted, on lease, 314 hectares of government land.

Over the past seven years, over 204,000 trees of different species converted the abandoned land into a dense patch of forest. But only a few weeks ago, the stillness of the night was shattered as many an axe fell on the woodlot. A group of a hundred people was felling the trees indiscriminately. By dawn, the felled wood was hidden in people’s cowsheds and the eaves of their houses.

The power-struggle between two factions in the village triggered one of them to cut down all the trees, and although everyone knew who was behind it, no one would utter a word for fear of retribution. Eighty women members of the co-operative society had the courage to complain and bring matters to the police, but the damage had already been done, and the forest co-operative is on the verge of collapse.

Risks and rights

This case is far from unique. Forest farms on previously bare land create a considerable economic value. It is therefore important that legal tenure rights are clearly defined beforehand to prevent conflict. Before initiating forest co-operatives it is thus important to assess if the group has (or can have) the legal right over the capital value of the trees on the land. Who is a legal member of the group, and how can this member claim his or her forest shares?

The contribution of tenure rights is best shown by a practical example from another state. In the early 1990s, the Forest Department in Haryana decided to lift the ban on felling and selling a few fastgrowing tree species. Farmers started planting poplar trees along their fields. Within ten years, Haryana has become a centre of plywood manufacturing with an estimated 50,000 trees being brought to the market every day. Farmers and the environment benefit accordingly.

Projects and programmes around the world are finding ways to compensate farmers for the services that trees can bring and the co-operative model is showing clear results. It is also showing, however, that farm forests are still constrained by existing laws and regulations. Disappointingly, programmes like the Green India Mission do not yet acknowledge the role of forest co-operatives in increasing the presence of trees on non-forest lands. In the coming year, the forest co-operatives will demand recognition of farm forestry and the provision of a legal and institutional framework that can help them scale up and replicate their initiatives across the country.

Text: Sudhirendar Sharma

Sudhirendar Sharma (sudhirendarsharma@gmail.com) works at The Ecological Foundation in New Delhi, India and researches and writes on environment and development issues. The author wishes to thank and acknowledge the inputs from Dr H.C. Gena, Project Manager, IFFDC, New Delhi, for his help in writing this paper.