In 2009, Mabomo and Mungaze, two communities in Gaza Province, southern Mozambique, welcomed the idea of a small project – and were surprised when asked to participate in the design and implementation of a Participatory Monitoring and Evaluation (PME) system around it. This system has promoted learning and empowerment among the members of these two communities, something that is now reflected in their consensus building approach to decision-making and actions.

The Gaza province covers a semi-arid area where cultivation is mainly rain fed. Access to land is not a constraint, but there is little infrastructure and rainfall is irregular, so yields are low. In the communities where we worked crop production is said to have failed in seven of the past 10 years. With increasing climate variability, agriculture contributes less and less to peoples’ incomes, and food security is increasingly at risk.

The Gaza province covers a semi-arid area where cultivation is mainly rain fed. Access to land is not a constraint, but there is little infrastructure and rainfall is irregular, so yields are low. In the communities where we worked crop production is said to have failed in seven of the past 10 years. With increasing climate variability, agriculture contributes less and less to peoples’ incomes, and food security is increasingly at risk.

A collaborative process

Our work was part of a large project that aimed to “increase the adaptive capacity of agro-pastoralists to climate change”. Building on collective action and social learning, its objective was to enhance the potential of farmer associations and communities to take action and reflect upon the outcomes of their work, paying special attention to the need to adapt to a changing context. The farmer associations first looked at a set of possible “adaptation options” which were to be selected in accordance with each group’s internal regulations and decision-making procedures.

Initially, community members seemed more interested in technical solutions such as developing an irrigation scheme, or a well in the pasture area. These options were rejected after an analysis of the resources that would be needed, the costs involved and the conflicts that could possibly arise. More attention was then given to those “knowledge intensive” options which could improve food security and resilience. The visit to a nearby research centre helped in defining the associations’ action plans that finally consisted of goat keeping, a revolving loan scheme, training courses for a community animal health worker, and the purchase of veterinary supplies.

The selection of these options was based on specific criteria: goat keeping was chosen in Mabomo because of these animals’ rapid reproduction rate, and because of the local commercialisation possibilities, and it was seen to form the basis for the group’s development beyond the project. The revolving loan scheme was given top priority in Mungaze as villagers thought that it could be used by less favoured members as an aid to ensure food security when crops have failed, serving as a safety net for all community members.

Learning through a PM&E system

| What to look at? | |

| (I) management | • are participants able to use the system themselves? • has the system become part of their regular activities? |

|---|---|

| (II) usefulness | • is the information collected useful? • is it helping them to achieve their aims? • is the information gathered responding to the perceived needs? |

| (III) appropriateness | • is the PM&E system fostering reflection? • is the analysis leading to new knowledge? |

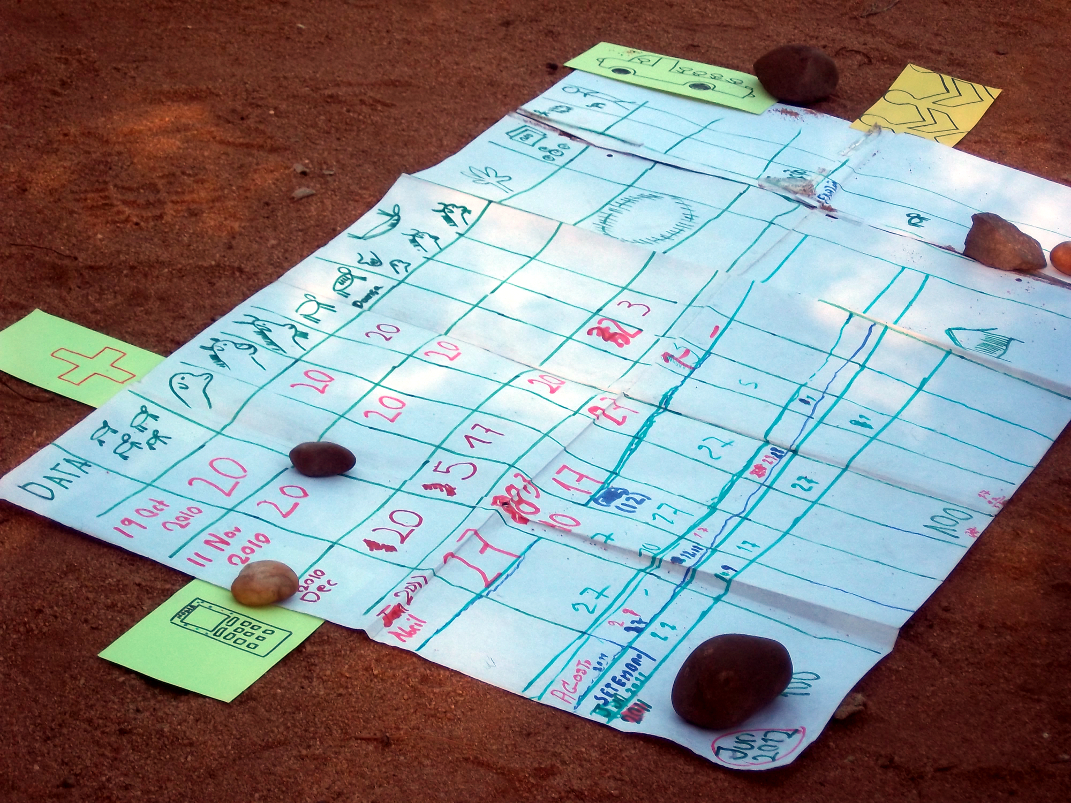

In 2011, about a year after our activities began, we started working on the development of an PM&E system which could be handled, and used, by the association members.

Our main objective was to build a tool that would help us all assess the results of the small-scale experiments that had started, and which would show if these were being successful or not. In short, we wanted to learn about the outcomes of the group activities, identifying constraints and improvement options, and also learn about the way in which these groups were working together.

We planned a five-step process which involved focus groups, interviews and general meetings. A series of planning meetings helped community members to come up with the main evaluation questions, and also identify the best indicators to measure results.

We were interested not just in collecting information, but also analysing it, and in using the results to modify or improve the loan scheme and the goat rearing efforts.

Moreover, we were interested in the trust that would be built through this process, thereby possibly strengthening both groups. One of our objectives was to have the process run and managed by the community members themselves. This meant focusing on a series of principles: inclusiveness, participation and collaboration, feedback and discussion, and reflection.

From the very first meeting we also saw that we needed to be context specific; that we had to find a balance between formal and informal meetings and discussions; and that the whole process had to be iterative. The PM&E system turned out to be combination of formal protocols and informal processes, helping us collect and share information, and take action: “The PM&E system has good information, because from it we can control the activity and see if something is not working right to improve it” (Antonio Tivane, group member, Mabomo).

Evaluating the PM&E

In a narrow sense, the PM&E tool was meant to look at the activities undertaken and at the results of the two “adaptation options”. But the collection of information and its analysis also helped us assess the effectiveness of the PM&E system, and its contribution to the community-based activities. The main principles behind our system, like inclusiveness, participation and co-operation, were assessed with semi-structured interviews, focus groups, a detailed SWOT analysis and participant observations, paying specific attention to the perceptions of all community members, the overall compliance with the internal rules and regulations, or the general participation levels.

Our analysis of the process showed that the iterative character of the PM&E system helped community members evaluate their work, and identify alternatives when something was not working. The M&E process also uncovered general problems, such as the difficulties that communities have in organising general meetings. In short, the process showed that community members learnt about the importance of collective action and learning, while community leaders claimed that they had improved their management skills. But it also helped them to identify the key elements that need to be included in every M&E system. The close link between gathering information and the collective decision-making process surrounding their “adaptation options” helped all community members recognise the importance of

- (a) meetings and group discussions, all of which enhanced transparency and accountability;

- (b) collective action and the need for internal governance procedures;

- (c) implementing activities with both short-term and long-term benefits, as a way to maintain motivation among members;

- (d) having plans that are collectively started and implemented so that all members benefit.

Together with an efficient decision-making processes and adequate leadership, the M&E process also increased trust and strengthened all community-based activities.

Empowerment through learning

While the M&E system was to help us all come to better “adaptation options”, it also promoted learning and empowerment. What we saw in Mabomo and Mungaze is that such a process motivates community members to take action by themselves, something which, in turn, strengthens local capacities. At the same time, the PM&E process introduced a motivational aspect that acted as a positive feedback to collective activities.

It encouraged both groups to continue with their activities and with the PM&E system itself – even when the “option” being tried, as in Mungaze, was not entirely successful. “We learnt to do things in practice and in thinking. We have been planning and doing, and that’s the most important thing I have learnt” (Maria Ngulele, Treasurer , Mabomo).

| Step | Aspects | Dates |

|---|---|---|

| Planning | • review of the main activities to be analysed; • review of the reasons behind an PM&E system; • formation of an PM&E team |

April – May 2011 |

| Deciding about the PM&E focus | • identification of the information needed • development of evaluation questions |

April |

| PM&E System development | • identification of the best indicators to use • development of an action plan |

May |

| Collection of information and analysis |

• focus groups, (semi-structured) interviews, observations • analysis |

May – June |

| Presentation of M&E results | • general meeting | July 2011 |

Two years after these groups started working together, those in Mabomo expressed a sense of pride which grew after they assisted those in Mungaze to evaluate their own collective activities. A joint learning process was established, during which community members shared ideas and experiences, and re!ected upon their successes and failures. Through a member-to-member exchange of experiences, Mungaze’s members learnt about the possible long-term benefits of working collectively and decided to try again by focusing on the other “adaptation options” that they had identified (training community animal health workers, purchasing veterinary supplies and a communal goat herd).

In both Mabomo and Mungaze, community members not only learnt about the outcomes and applicability of possible adaptation options, but also about the advantages of working together in assessing outcomes, and enhancing them. “Together we can go far, individually it is not so easy” (Jose Cumbulela, Secretary, Mabomo).

María José Restrepo Rodríguez, Claudia Levy and Brigitte A. Kaufmann

María José Restrepo Rodríguez (majorestre@gmail.com), Claudia Levy and Brigitte Kaufmann are part of the German Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Agriculture (DITSL), in Witzenhausen, Germany. Their work was part of the collaborative project funded by BMZ and ILRI, “Supporting the vulnerable: Increasing the adaptive capacity of agro-pastoralists to climatic change in West and Southern Africa using a transdisciplinary research approach”. María José Restrepo Rodríguez and Claudia Levy worked in Mabomo and Mungaze as part of their M.Sc. and Ph.D. studies.

References

Estrella, M. and J. Gaventa, 1998. Who counts reality?: Participatory monitoring and evaluation: a literature review, IDS Working Paper 70, Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, U.K.

Restrepo, M., 2011. Assessment of community based activities through the implementation of a participatory monitoring and evaluation system. Master’s thesis. Universities of Goettingen and Kassel, Germany.

Levy, C., S. Moyo, C. Hülsebusch, E. Webster and B. Kaufmann, 2010. Processes of change: Climate variability and agro-pastoralists’ livelihood strategies in Gaza Province, Mozambique. Tropentag 2010, Book of Abstracts. Zurich, Switzerland.