Even in the International Year of Family Farming there is confusion about family farming. What is it, and what distinguishes it from entrepreneurial farming or family agribusiness? The confusion tends to be highest in places where the modernisation of agriculture has led society further away from farming. Jan Douwe van der Ploeg takes us into the world of family farming, which he says is considered to be “both archaic and anarchic, and attractive and seductive”.

What is family farming?

(www.boerderijbuitenverwachting.nl). Photo: Bob van der Vlist

For many reasons, family farming is one of those phenomena that Western societies find increasingly difficult to understand. One of these reasons is that family farming is at odds with the bureaucratic logic, formalised protocols and industrial rationale that increasingly dominate our societies. This makes family farming into something that is seen, on the one hand, as archaic and anarchic, whilst at the same time it emerges as something attractive and seductive.

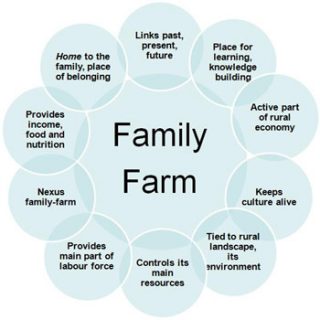

Family farming is also difficult to grasp because it is a complex, multi-layered and multi-dimensional phenomenon. Below, I identify ten qualities of family farming. These qualities are not always present at the same time in every situation. The most important thing to remember is that the reality of family farms is far richer than the two single aspects that are most commonly used to describe them: that the farm is owned by the family and that the work is done by the family members.

Family farming is not just about the size of the farm, as when we talk about small scale farming; it is more about the way people farm and live. This is why family farming is a way of life.

A balance of farm and family

Let’s take a look at these ten qualities. First, the farming family has control over the main resources (1) that are used in the farm. This includes the land, but also the animals, the crops, the genetic material, the house, buildings, machinery and, in a more general sense, the know-how that specifies how these resources need to be utilised and combined. Access to networks and markets, as well as co-ownership of co-operatives, are also important resources.

Family farmers use these resources not to make a profit, but to make a living; to acquire an income that provides them with a decent life and, if possible, allows them to make investments that will further develop the farm.

In addition the family farm is a place where the family provides the main part of the labour force (2). This makes the farm into a place of self-employment and of progress for the family. It is through their dedication, passion and hard work that the farm is further developed and that the livelihood of the family is improved.

The farm is there to meet the many needs of the family, whilst the family provides the possibilities, the means and also the limitations for the farm. This nexus between the family and the farm (3) is at the core of many decisions about the development of the farm. Each particular farm has its own specific balances, for instance between the mouths to be fed and the hands to do the work. These balances tie family and farm together and make each family farm into a unique constellation.

Linking past, present and future

But there is more than ownership and labour. Family farms provide the farming family with a part (or all) of its income and food (4). Having control over the quality of self-produced food (and being confident that it is not contaminated) is becoming increasingly important for farmers around the world. However, the family farm is not only a place of production (5). It is also home to the farming family. It is the place they belong to, as much as the place that gives them shelter. It is the place where the family lives and where children grow up.

The farming family is part of a flow that links past, present and future (6). This means that every farm has a history and is full of memories. It also means that the parents are working for their children. They want to give the next generation a solid starting point whether within, or outside, agriculture. And since the farm is the outcome of the work and dedication of this and previous generations, there is often pride. And there can also be anger if others try to damage or even destroy the jointly constructed farm.

The family farm is the place where experience accumulates (7), learning takes place and knowledge is passed on, in a subtle but strong way, to the next generation. The family farm often is a node in wider networks in which new insights, practices, seeds, etc., circulate.

Tied to its environment

The family farm links past, present and future. Photo: Badstue / LEISA ArchiveThe family farm is not just an economic enterprise that focuses mainly, or only, on profits, but a place where continuity and culture are important. The farming family is part of a wider rural community, and sometimes part of networks that extend into cities. As such, the family farm is a place where culture is applied and preserved (8), just as the farm can be a place of cultural heritage.

The family and the farm are also part of the wider rural economy (9), they are tied to the locality, carrying the cultural codes of the local community. Thus, family farms can strengthen the local rural economy: it is where people buy, spend and engage in other activities.

Similarly, the family farm is part of a wider rural landscape (10). It may work with, rather than against nature, using ecological processes and balances instead of disrupting them, thus preserving the beauty and integrity of landscapes.

When family farmers works with nature, they also contribute to conserving biodiversity as we see in Andhra Pradesh and to fighting global warming. The work implies an ongoing interaction with living nature – a feature that is highly valued by the actors themselves.

Freedom and autonomy

The family farm is an institution that is attractive as it allows the farm family a relative degree of autonomy. It embodies a “double freedom”: there is freedom from direct external exploitation and there is freedom to do things in your own way.

In short, family farming represents a direct unity of manual and mental labour, of work and life, and of production and development. It is an institution that can continue to produce in an adverse capitalist environment,just as anaerobic bacteria are able to survive in an environment without oxygen (I am grateful to Raúl Paz from Argentina who coined this nice metaphor).

Why is it important?

Given all these features, family farming can make a strong contribution to food security and food sovereignty. It can strengthen economic development in a variety of ways, creating employment and generating income. It strengthens the economic, ecological and social resilience of rural communities. It offers attractive jobs to large parts of society and can contribute considerably to the emancipation of downtrodden groups in society.

Family farming can also consistently contribute to the maintenance of beautiful landscapes and biodiversity.

External threats

However, it may turn out to be impossible to effectively realise all these promises. This is particularly the case these days, when family farming is being squeezed to the bones and becoming impoverished.

When prices are low, costs are high and volatility makes medium or long term planning impossible, and when access to markets is increasingly blocked and agricultural policies neglect family farmers, and when land and water are increasingly grabbed by large capital groups – in such circumstances it becomes impossible for family farmers to provide positive contributions to society at large.

This is why we have now ended up in the dramatic situation that the land of many family farmers is laying idle. Or, to use a macro indicator, that 70% of the poor in this world today, are rural people.

Internal threats

There are internal threats as well. Nowadays it is en vogue to talk about the “need to make family farming more business-like”, in other words that it should be oriented towards making profits. Some even argue that this is the only way to keep young people in agriculture. According to this view, family farming should become less “peasant-like” and more “entrepreneurial”, and family farming in the global South should be subject to a similar process of modernisation that has occurred in the North.

A part of European agriculture has indeed changed towards entrepreneurial farming. This has effectively turned the family farm into a mere supplier of labour, at the expense of all the other features mentioned above. Formally, these entrepreneurial farms are still family farms, but in substance they are quite different. One major difference is that “real” family farms grow and develop through clever management of natural, economic and human resources, and through (inter-generational) learning. Entrepreneurial farms mostly grow through taking over other family farms. This tendency to enter into entrepreneurial trajectories is a major internal threat to the continuity and dominance of family farms. And we see it nearly everywhere.

Re-peasantisation

“Family farming represents a direct unity of manual and mental labour, of work and life, and of production and development.”

However, there are important counter-tendencies. Many family farms are strengthening their position and their income by following agro-ecological principles, by engaging in new activities, or by producing new products and new services – often distributed through new, nested markets.

Analytically these new strategies are defined as forms of re-peasantisation. They make farming more peasant-like again, but at the same time they strengthen the family farm, as can be seen in the example of re-peasantisation in Spain. Re-peasantisation is way of defending and strengthening family farming.

What is to be done?

The policy environment is extremely important for the fate of family farming. Although family farming can survive in highly adverse conditions, positive conditions can help family farming reach its full potential. This is precisely the reason that the policies of state apparatuses, multinational forums (such as the FAO, IFAD and other UN organisations), but also of political parties, social movements and civil society as a whole, are so important.

Policy can ensure that family farmers’ rights are secured and that sufficient investments are made in infrastructure, research and extension, education, market channels, social security, health and other areas. This provides farmers with the security to invest in their own futures, as recently reconfirmed by the prestigious High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition.

Strengthening rural organisations and movements is also of great importance. We have to keep in mind that, all around the world, family farmers are trying to find and unfold new responses to difficult situations. Thus, identifying successful responses, building on novel practices, communicating them to other places and other family farmers and linking them into dynamic processes of change must be central items on our agenda. In short: much needs to be done. The good news though, is that every step, no matter how small, is helpful.

Jan Douwe van der Ploeg

Jan Douwe van der Ploeg is professor of Rural Sociology at Wageningen University and at China Agricultural University in Beijing.

E-mail: JanDouwe.Vanderploeg@wur.nl or visit www.jandouwevanderploeg.com