Rural–urban linkages connect people in cities with people in the countryside on a daily basis. The links are tangible and include markets, migration flows, knowledge exchange, leisure and tourism, ecosystem services, food production and consumption. To support sustainable, fair and resilient food systems, an enabling political and institutional environment is needed. This ‘twin’ issue of Farming Matters and Urban Agriculture Magazine, produced together by ILEIA and the RUAF Foundation, looks at some existing experiences with strengthened rural–urban linkages and what they teach us about improving food systems for both consumers and agroecological farmers.

The role of both rural and urban spaces for rebuilding food systems is ever more relevant today. Cities are growing and globalisation is impacting everyone, producers and consumers alike. Hunger, malnutrition, unhealthy diets and obesity affect billions of people, soil degradation affects billions of hectares, and we face an alarming climate crisis. In this context, our food systems – how our food is produced, where, and how it ends up on our plates – must be rethought. From a production perspective, we need to value agroecological approaches and family farming as a way of life. From a consumption perspective, we need enough safe, nutritious and culturally appropriate food for everyone and to break out of non-resilient patterns of urban development.

Many debates on rural and urban development have remained rather dislocated. The city was mainly conceived as a far-away place where consumers had to be reached with ‘market access’ programmes but very little real connections were established between producers and consumers. Rather, the role of rural areas was reduced to a supportive one: feeding cities with cheap food. Policies pushed for intensive industrial agriculture, disconnecting people from their food and leaving room for middlemen, large distributors and retailers to take control over ever larger parts of the food chain. Decision makers in cities were hardly concerned about the ecological impacts of urban development for their peri-urban and rural surroundings, and saw no role for themselves in developing policies to influence food consumption and production patterns of their inhabitants. But all of this is rapidly changing, and there is growing awareness that improved rural–urban linkages are an essential element in the necessary transition towards more sustainable and resilient food systems. This is seen in joint initiatives by farmers and urban-based consumer groups for concrete changes that span across the urban–rural divide, with examples in this issue.

The important role of rural–urban linkages is also increasingly recognised through policy as a key factor for the development of sustainable, healthy and resilient food systems. That more than half of humanity now lives in cities, and that this share is likely to increase further in the coming decades, especially in Africa and Asia, has shifted policy priorities and introduced new actors. Concerns over climate change, resilience to environmental and economic shocks, food security and health have put food firmly on urban agendas. Cities have become important policy actors on food issues, and many have developed their own urban food policies in an area that was traditionally dominated by rural and agricultural policies. Likewise, civil society organisations in cities increasingly take up activities around urban agriculture and food, either for reasons of gastronomy or for environmental, social and health concerns, thereby building bridges between the rural and urban.

But where does the rural stop and where does the urban start? This is difficult to answer as the boundaries between city and countryside, or urban, peri-urban and rural, are ever more blurred. Rural and urban spaces cannot and should not be categorically separated. They are intimately linked and recognising and further strengthening these linkages is an important starting point for building viable pathways to sustainable and resilient food systems.

Dual identities

With rapid and increasing urbanisation, what does it mean to be urban? The move from rural to urban is often a result of necessity. National and international policies that favour industrial types of agriculture make it more difficult to continue family farming, pushing people to the cities, who can then send money to support those who stay on the farm. Pablo Tittonell points out that such ‘safety nets’ enable many farmers to continue producing when sole reliance on farming is no longer an option, but that this also works both ways, with urbanites in turn depending on traditional and diverse foods from their rural families.

These mutual relationships, made possible by urban people holding firmly to their rural identities, transcend individual families and rural–urban divides, and can manifest themselves as class-based alliances. Bolivian domestic workers fighting for food sovereignty is one such example where city dwellers, often recent migrants from the countryside, work together with peasants to create alternative food systems.

Strong rural identities in an urban context are also seen among growing numbers and increasingly varied urban agriculture initiatives. Such ‘rural’ activities in cities serve social needs, provide food security, and income-earning opportunities in marginalised communities. City farmers in black townships in South Africa introduce elements of rural lifestyles such as a sense of place and community ties in the urban context. Urban agriculture is also political, and citizens are fighting for control over their food systems and for recognition as urban farmers. In many cases, these objectives overlap, as in Rosario.

Counterforces

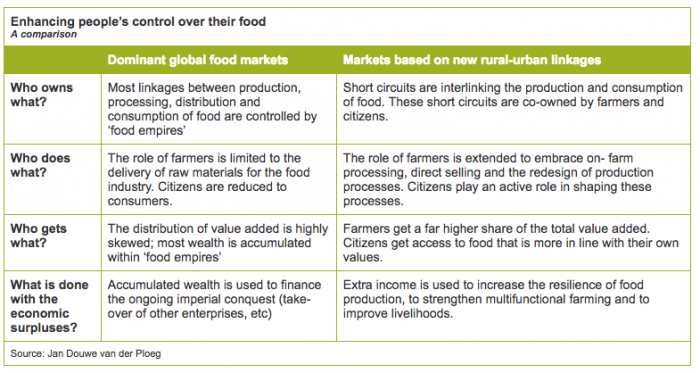

Even with hostile market and policy environments and increasing urbanisation, family farmers provide 70% of the world’s food. ‘Feeding the world’ is no small task, but citizens are not passively being fed, they are actively shaping how their food is produced and by whom (see box), ever more preferring food from family farmers. For this reason, farmers and consumers build new connections and start to collaborate.

Innovative direct marketing arrangements are an important link between farmers and consumers that contribute to overcoming the rural–urban divide. Shortening value chains, and developing direct relationships between farmers and consumers is gaining ground, and the strongest and most successful are those where the new social relationships are much more than a mere economic exchange. They include trust, friendship and new communities, as seen in initiatives that circumvent the strongly globalised food system in the Netherlands. Community Supported Agriculture, an alternative food system popular in Japan and the USA, spreading rapidly to Europe and also emerging in the global south, is a good example. In China, this concept is popular, providing consumers with reliable and safe food while also supporting young farmers to produce ecological food and pursue a lifestyle of their choice.

Besides direct marketing arrangements that build social networks, other initiatives that strengthen relationships and cooperation between farmers and citizens also emerge, founded on mutual benefits and often with shared or converging goals. For instance, across Japan, a system of shared ‘ownership’ supports farmers and urbanites to work together to preserve their highly valued but threatened rice terraces. Farmers share their traditional knowledge to preserve cultural landscapes and revive their rural communities, while people from the city want to learn about farming and educate their children.

Although the net flow of people is from rural to urban areas, there is an emerging counter-flow. Young people in particular are moving from cities to start farming. These so called ‘new farmers’ or ‘neo-rurals’ are motivated by social and environmental concerns and often choose agroecological practices. This is happening in many different parts of the world, and concepts such as Community Supported Agriculture, as in China and (peri-)urban farming, as in Brazil, are part of this dynamic.

Governance structures for agroecology

Agroecology is a consistent thread in building stronger rural–urban linkages. It is striking that urban agriculture initiatives like those in Argentina and South Africa explicitly choose agroecology as a point of departure, both in terms of production methods and for social and market relations that these initiatives embody. Also, several urban-based initiatives aim at closing nutrient and water flows at the local level, thereby improving the ecological ‘metabolism’ of the city. This shows that agroecology is as much the domain of the urban as it is of the rural. We see a convergence between rural- and urban-initiated movements, showing that consumers and producers alike have a stake in agroecological food production. Besides safe and healthy food, sustainable farming offers other benefits such as protection of cultural and environmental landscapes, carbon storage, biodiversity and clean water which city dwellers demand. Ecosystem services provided by farmers to cities deserve particular recognition.

A common denominator of the successful examples highlighted in this issue, is that they all have succeeded in putting into place appropriate social networks and institutional arrangements needed to add value to and strengthen the potential of rural–urban linkages. These range from marketing structures like Community Supported Agriculture or ‘food hubs’, social mechanisms that mobilise voluntary labour and initiatives that provide required knowledge, support and exchange. These structures allow citizens and farmers to govern their food according to their own values and principles. Without such governance structures that interconnect and strike the right balance between key rural and urban actors, improved rural–urban linkages would not be possible.

New and international policy making arenas are embracing the importance of rural–urban linkages, as seen in this issue. These pages provide examples from across the world, where citizens, farmers, consumers, workers, women and youth, are building new, and strengthening existing rural–urban linkages with positive and concrete benefits. While these practices are promising, many challenges remain and still need to be addressed. On the one hand, it is key that international and national policies create space for emerging alternatives, Biraj Patnaik demonstrates for the World Trade Organisation that this is not always the case. On the other hand, we must make sure that rural–urban linkages continue to be grounded in practice, to avoid that it turns into another new buzz-word. For this, the active engagement of citizens, both consumers and producers, is the best way to create new pathways towards sustainable food systems we so urgently need.

Madeleine Florin (ILEIA) and Henk Renting (RUAF)