The Harvest of Hope initiative is a vegetable box scheme in Cape Town, South Africa, set up as a social enterprise by a local ‘social profit organisation’. By promoting ecological urban farming, Abalimi Bezekhaya (meaning ‘Farmers of Home’ in Xhosa) improves income and household food security, and empowers disadvantaged households by building their confidence and capacities in farming. Building a sense of place and strengthening community ties, neither so common in South Africa’s urban areas, are keys for success of this approach.

Established in 1982, Abalimi has for 33 years been working with urban small scale producers to develop their own ecological vegetable gardens in Khayelitsha and Nyanga townships and surrounding Cape Flats areas (www.abalimi.org.za). Abalimi provides support services, supplying compost, seed, seedlings, marketing, sales support, training, extension, support for monitoring and evaluation, development of local networks and partnerships, and building community organisations.

The work of Abilimi contributes in different ways to food security and strengthening of livelihoods in the townhips. Initially, Abalimi started working with disadvantaged women, engaging them in vegetable production in home and community gardens to improve household food security. When some produced a surplus, they started selling ‘over the fence’ to their neighbours. They wanted to access new markets beyond their local community as they did not see their local markets as large or reliable enough, though they lacked the capacity to do so on their own. Abalimi had been experimenting with marketing inside and outside the townships for seven years, and started the Harvest of Hope initiative to support the development of supply chains to local markets.

Subsistence and market-oriented production

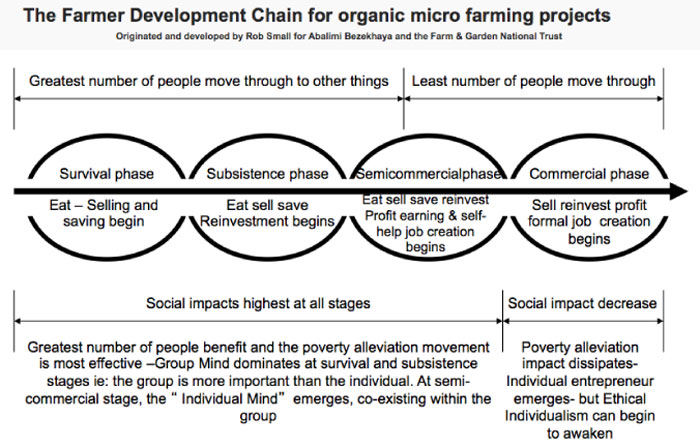

According to Abalimi, farm development schemes often make the mistake to assume a contradiction between subsistence farming and market-oriented food production. Conventional farm development tries to pull the urban poor into commercial production, forgetting that many or most don’t want to be full time producers. Through experience, Abalimi found that farmers apply a range of different strategies and tools to improve their food security and sovereignty, and developed the ‘development chain’ methodology to assist farmers’ groups to choose the strategies that best fit their specific situations.

The methodology has four phases: the survival, subsistence, livelihood and the commercial phase. Producers or producer groups can remain in any phase permanently, or move between phases. In each, producers need different types of support, from basic training on how to grow vegetables, to learning how to plan for regular production throughout the year.

A crucial aspect is that producers first need to become sustainable and stable at each development stage before deciding to move up to another that is more complex and demanding, and especially before deciding to take on a serious commercial element. For producers to sustainably move between stages, a step-wise approach is needed, that addresses socio-political, environmental and economic difficulties encountered on a daily basis. These include, among others, poor education, poverty, mentality, gender, racial and class tensions, very poor soil, and mass unemployment.

Harvest of Hope

The Harvest of Hope initiative was set up by Abalimi in 2008 to develop short marketing chains that would support the move from subsistence farming to (semi-)commercial farming (www.harvestofhope.co.za). It is a marketing system selling boxes of ecologically grown, seasonal vegetables on a weekly basis, with the following objectives.

Providing a sustainable and growing market for urban micro-farmers from the townships;

- Using this market as an engine for poverty alleviation, enabling township farmers to have dignified, sustainable livelihoods.

- Giving customers access to fresh ecological produce with less food miles and at competitive prices.

- Ensuring that fresh ecologically produced food is available year round for producers, their families, and local communities.

Harvest of Hope was launched in partnership with the South African Institute for Entrepreneurship (SAIE) and Business Place Phillipi, with support from the Ackerman Pick n Pay Foundation. The initial investment was used to renovate and upgrade the packing shed, develop training materials, to design and launch the brand, and train staff. Starting with eight producer groups, Harvest of Hope was working with 18 groups and around 120 producers after three years. The weekly food box membership increased from 79 in 2008, to 350 in 2012, and some 450 boxes in early 2015, with vegetables produced in 29 paid up member gardens and 43 non-member gardens (ad-hoc suppliers). About a quarter of Abalimi’s producer groups supply Harvest of Hope boxes.

This is a clear example of a social enterprise combining community empowerment with economic market development. The main beneficiaries are the vegetable producers, mostly older women and some dedicated younger producers, as well as the customers. There are similar organic vegetable box schemes elsewhere in Cape Town, such as Wild Organic Foods, Ethical Co-op and SlowFood, but these do not have the same focus on social community development and not-for-profit philosophy.

Harvest of Hope manages the packaging, marketing and selling the products, while Abalimi supports producers with technical support, production plans, provision of seeds, organic fertilizers, and the maintenance and repair of irrigation equipment. Harvest of Hope has a full-time marketing manager and a team of part-time staff consisting of field workers, a book keeper, packers and drivers.

Consumers subscribed to the vegetable box scheme collect their boxes from any of 25 collection points around Cape Town, usually schools, university buildings, business and government offices, and friendly shops. They target educated, middle class and socially responsible consumers, with new customers attracted mostly through word of mouth and social media, though there are also weekly garden tours.

Harvest of Hope does not have official organic certification as requirements are very strict and take at least three years. But they use their own standards whereby no artificial chemicals, pesticides, herbicides and fertilizers are used, and are in the process of setting up a participatory guarantee system, a locally focussed quality assurance system that certifies producers based on the active participation of stakeholders.

Growing sense of place and community

Harvest of Hope is an initiative with an urban background in Cape Town townships, but its dynamics and success are strongly based on urban–rural relations. Up to half of the disadvantaged black population in Cape Town have roots and have migrated from nearby rural areas, especially the Eastern Cape. And, their rural roots and the associated rural–urban links are still very much alive. Amongst the producers within Abalimi and Harvest of Hope, about 60% regularly spend weekends and summers in their rural areas of origin. Also, it is common amongst those who made a good living in the townships to return to their rural home communities after retirement.

Rural–urban linkages are also important in terms of farming practices and agroecology. There are frequent reports from fieldworkers about the exchange of seeds, seedlings and cuttings used within Abalimi’s programmes, bought from the Abalimi Garden Centres in Nyanga and Khayelithsha and taken back to the Eastern Cape. There is also a counter-flow of traditional crop seeds of rainbow maize, beans and melons, from rural areas to Abilimi’s gardens. A good example of this is Mama Mabel Bokolo who runs the Abalimi People’s Garden Centre in Nyanga. Ma Bokolo regularly grows saved seed from her rural home to generate new seed stock, saying that “I plan to return permanently to the Eastern Cape in 2017, and I want to promote the Abalimi way in my rural home.”

The experiences of Abalimi and Harvest of Hope build on the strengthening of links between the ‘urban’ and the ‘rural’. Harvest of Hope was intended as a means to join forces between producers and engaged consumers, with the concept of community supported agriculture as a guiding principle. This strong community development-orientation is one of the factors that differentiates Harvest of Hope from more commercially-oriented vegetable box schemes in the area.

Abalimi’s and Harvest of Hope’s activities help to introduce elements of community organisation and ‘rootedness’ in the land, to the black townships of Cape Town, two things uncommon to South Africa’s urban areas. City people in South Africa are often strongly individualised and focused on competitive notions of entrepreneurship, whereas social life in the countryside is managed around community ties and clan relations. This sometimes results in tensions and difficult life choices, as with the young farmer leader Xolisa Bangani, 25 years old, and next in line to a clan chieftainship in the Eastern Cape. He is contemplating taking up this responsibility, but first wants to develop his own organisation in Cape Town and gain life experience. As such, activities of Abalimi and Harvest of Hope centred on agriculture and food, manage to blend socio-cultural and lifestyle elements across the rural–urban divide and combine the best of both worlds.

Rob Small and Femke Hoekstra

Rob Small is a co-founder of Abalimi and Harvest of Hope, he is the founder of www.farmgardentrust.org which supports and promotes Abalimi and Harvest of Hope as a national role model.

Email: info@farmgardentrust.org

Femke Hoekstra is the knowledge and information officer at RUAF Foundation.

Email: f.hoekstra@ruaf.org