Adivasi communities in India have come together to collectively represent their cultural, agronomic and climatic calendar as they know it. Youth have been using the life cycle to reflect on the effects of climate change and people’s responses to it. This is a case of collective learning that reflects indigenous worldviews.

Dialogue amongst the different members of The Food Sovereignty Alliance, India resulted in co-creating knowledge, strategies and actions to strengthen our food sovereignty and cope with climate change. The Food Sovereignty Alliance, India works to reclaim and democratise local community control over food and agriculture systems . Members of our alliance include organised groups of Dalit people, Adivasis, small and marginal farmers, pastoralists, and co-producers. The co-producers are a political constituency of the alliance, who may not be directly engaged with food production themselves, but work in solidarity with the Alliance. Co-creating knowledge is a key element in our movement through which innovative and creative solutions emerge. I share one such example through this article in which, through co-creation of knowledge, we developed our own way of assessing the impacts of climate change and strengthening our coping strategies in our villages.

Rejecting top-down solutions

The establishment of REDD/ REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation programme), in 2010, as a key strategy to combat climate change, has been applauded by world leaders. In practice, REDD entails sinking carbon in standing stocks of trees, and raising new plantations, often on indigenous territories. From previous such models of carbon trade that had been tested in their territories, indigenous peoples were aware of how such policies and programs alienated Adivasis from their territories and forests. They had been forced to relinquish customary practices and forest governance, undermining indigenous resilience and climate coping strategies and threatening local food sovereignty.

An indigenous alternative

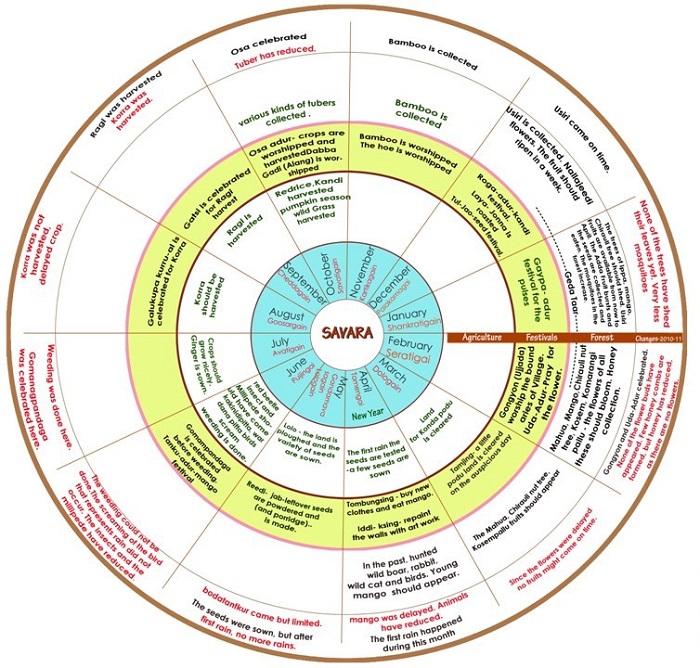

In 2010, Adivasi Aikya Vedika, a member of the Food Sovereignty Alliance, was invited by the Indigenous Peoples Biocultural Climate Change Assessment (IPCCA), to join a global initiative of indigenous peoples to assess climate change impacts and also to develop indigenous peoples’ response strategies to extreme climatic events drawing from their knowledge, experience, wisdom and worldviews. The Adivasi community became deeply involved in identifying a framework of enquiry to facilitate local assessments of climatic impacts and response strategies. Intense dialogue amongst the different Adivasi communities and co-producers resulted in the idea of reconnecting with the indigenous rhythm of life or ‘life cycle’. This life cycle is a representation of how the community members live their lives, based on the Adivasi worldview. It describes their relationship to their territories, seasons, food, forests, and the cultural cycles of life, in time and space.

In the course of one of the dialogues, at a meeting of Adivasi elders and youth, different groups were busy drawing their communities’ life cycles on paper and we realised that this life cycle was in fact a lived, dynamic, indigenous epistemology that could be used by communities to assess and record the impacts of climate change in their indigenous territories and on their lives. There was tremendous excitement. Young people from the community took the lead in creating a collective vision of their communities’ cycle of life. They began working with both male and female elders of the community recording their narratives and memories in spoken word, art, poetry, stories or songs. They translated all of this onto paper and on their walls. There was unanimous consensus of a circular representation of the life cycle.

In the case of some of the indigenous communities there existed another layer of information of ‘how it was 70-80 years ago’, which came from existing literature. For instance, books about Gonds the Chenchus and the Konda Reddis, include intricate descriptions of people’s lives, centred around their relationship to their territories and seasonal cycles. This was used by the community as additional information about climatic events on the life cycle.

The life cycle in action

After illustrating the cycle as ‘we know it is’, according to the communities’ experience, the young folks of the community began to use the life cycle to assess in real time, the trends each year. This was done by recording what was happening in the present and comparing it with established life cycles. They compared the flowering and fruiting of trees, the appearance or not of birds and insects, the onset or delay of weather patterns, and sowing and harvesting cycles. They also used the life cycle to identify forces that threaten or strengthen indigenous resilience. Most significantly what emerged was that villages with strong functioning village councils were far more resilient than villages with poorly functioning village councils. For instance, village councils which had rejected plantations showed higher diversity of food crops and thus resilience to climatic changes, than villages where individual families were persuaded to replace food crops with plantations on their lands.

They used the life cycle to identify forces that threaten or strengthen indigenous resilience

The life cycles illustrate the resilience of communities in the face of climatic variability. For instance, in 2012, the Savara community of Bondiguda village recorded how in the month of Lologain (approximately, the month of May), the usual season to sow diverse food crops, rains were scarce (see Savara Adivasi Life cycle illustration above). Around the same time, the community recorded how the forest department tried to convince, and in many instances force, the community to raise tree plantations on their food crop lands, saying this would bring both money and rains. The constant refrain of the forest department is that growing trees will bring more rain. Discussions in the village revealed that despite the scarce rains and the pressures of the forest department, the village residents preferred not to establish tree plantations on agricultural land and instead continued to grow food. This continued planting ensured that there was food for the year, and seeds for the future. In this case, the life cycle exercise also made visible communities’ commitment to autonomous food production despite external pressures to use the land for other purposes.

The life cycle approach not only continues to be used by the Adivasi communities to develop the idea, but it has also been adopted in other territories. It has proven to be an extremely effective approach for a number of reasons. It readily captured impacts of climate change, but this was just the first step of the process. The life cycles have been a critical tool for communities to discuss their own lives and situations. They have been a means for the communities to understand their own resilience and to share their innovative adaptation strategies with each other.

The life cycle exercise also made visible communities’ commitment to autonomous food production despite external pressures to use the land for other purposes

They help communities to actively assert their knowledge and strategies in the wake of climate change, offering concrete proposals that build indigenous resilience as well as mitigate the effects of climate change. In other instances it also stimulated intense discussions on steps to be taken by the community to halt and prevent the entry of mining, dam and plantation projects.

Road ahead

A major challenge continues to be state and global policies that refuse to recognise these indigenous approaches and epistemologies as valid. States are still determined to push false carbon trade arrangements, such as REDD/REDD+ as the solution to climate change, despite evidence of another way forward based on Adivasi peoples worldviews and life practice. However, through the life cycles, communities are increasingly able to confidentally reject the government’s climate change proposals.

Dr Sagari R Ramdas

Dr Sagari R Ramdas (sagari.ramdas@gmail.com) is a veterinary scientist, a member of the Food Sovereignty Alliance, India, and is learning to be a farmer.