Over 50 crop species grow on farms in the Gamo Highlands. Farmers use this diversity to meet nutritional, cultural and production needs under variable conditions. In the face of population growth, increased access to improved seed, and cultural and political pressures, maintenance of crop diversity requires more attention than ever before. To this end, farmers and other actors are working to celebrate the region’s traditional crops and management strategies with the hope of preserving both the diversity and culture that depends on it.

The Gamo Highlands rise from the Ethiopian Rift Valley to elevations of up to 4000 metres. The heterogeneous mountain landscape and 10,000 years of cultivation have resulted in a diversified agroecosystem that includes annual and perennial cropping, agroforestry, and livestock. Agriculture revolves around enset (Ensete ventricosum), a perennial tree crop that serves as a staple food for seven to ten million people.

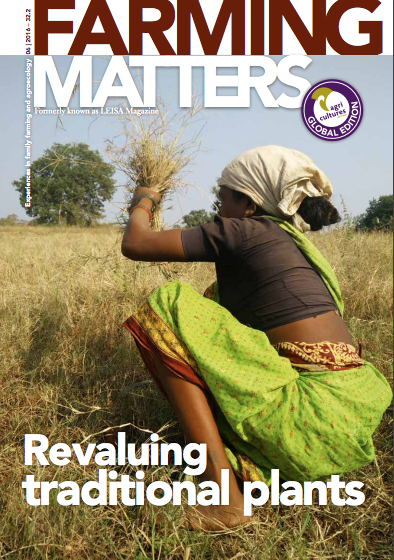

Farmers cultivate dozens of barley varieties

A traditional Gamo homestead is ringed by an enset plantation, a mixture of agroforestry trees, vegetable, and root crops. Beyond this ring are crop fields, parts of which are left fallow for use as private grazing land. Lowland crops, such as coffee, sugar cane, cassava, sweet potato, and yam extend to elevations of 2400 m or more. Mid-altitude crops such as taro, squash, wheat, peppers, and beans are present in all but the highest communities (above 2800 m), where enset, barley, cabbage, potato, and gade dono (Plectranthus edulis) dominate. Wild species are also tolerated on fallow fields and intercropped with cultivated species.

The Ethiopian highlands are a global centre of crop genetic diversity. Rich pools of genetic material help protect crops against pest and disease outbreaks, provide insurance in the face of variable condtions, and allow crops to adapt to a changing climate. Furthermore, this diversity helps maximise productivity, and allows farmers to meet a range of dietary and cultural needs. For example, farmers cultivate dozens of barley varieties, selected for their taste, colour, and texture and also to match specific soil types, elevation, moisture levels, and topography. Enset diversity is also very high, with more than 100 documented varieties in Ethiopia, and up to 60 varieties found in each Gamo community.

Traditional crops under threat

In the past decades, land shortages have worsened, forcing farmers to abandon traditional barley varieties, indigenous root crops, sorghum, and other staples. As farms shrink, government extension has increased promotion of improved seed and fertilizer packages, as well as fruit and vegetable crops for market. These packages are often components of larger programmes tied to development aid and combined with other incentives. Yet many farmers experience crop failure or cannot acquire necessary inputs in the years following initial adoption. In some cases farmers purchase these inputs on credit, and are unable to pay off their loans when crops fail, forcing them to sell livestock or drain savings.

In addition, several government and church interventions have damaged social institutions that allow farmers to manage and maintain crop diversity. For instance, enforced participation in work-for-food programmes along with new religious obligations have caused the breakdown of many traditional communal labour institutions. In addition to these social changes, enset crops are increasingly threatened by disease, likely related to rising temperatures and changes in rainfall patterns. In several lower elevation communities, bacteria that cause wilt disease (Xanthomonas campestris) have decimated enset plots.

Combining new and old

“We grow everything here but salt,” said a group of farmers from the mid-altitude community of Bele. In the Gamo, the highest on-farm crop diversity is found in mid-altitude regions, which provide a diverse source of products for lowland and highland farmers. Strong ties between communities at different altitudes underpin traditional systems of seed sourcing and exchange. Farmers travel long distances to acquire seed at local and regional markets, often at different elevations. Farmers who visit a greater number of markets are more likely to have higher crop diversity on their farms.

Although farmer managed seed systems are under pressure, farmers have found ways to augment, rather than replace, their traditional seeds. In addition to visiting local and regional markets, they also source seeds from government extension offices through aid programmes, trials, and credit packages. Farmers with more access to land and resources are more easily able to combine both traditionally- and formally-sourced seed. These farmers are often a source of seeds for their neighbours and family, in addition to selling surplus at local markets. Diversified options for sourcing seed allow farmers to experiment with new varieties. For example, one farmer may obtain maize varieties from lowland markets, barley varieties from high elevation markets, wheat from government extension, and fruits and vegetables from an aid programme.

Celebrating knowledge

By strengthening social institutions and drawing on their rich knowledge base, farmers and other actors counteract the threats to their traditional crops. “We already know how to farm,” said one farmer, reflecting the sentiments of many others who maintain traditional crops and view with scepticism the changes brought about from the top down. Cultural associations, such as CASE (the Culture and Arts Society of Ethiopia), educational institutions, and external organisations such as the Christensen Fund, host symposia, conferences, traditional festivals, and art and music exhibitions. These activities promote traditional crops and foods. However, the country’s political climate can impede the ability of these organisations to operate freely, or expand their reach.

Scientific and academic institutions also recognise the importance of Gamo farmers’ traditional agricultural knowledge. For example, Arba Minch University, in the valley below the Gamo Highlands, recently hosted an international symposium celebrating enset uses and diversity as part of the ongoing Enset Park project. The idea behind the Enset Park is to promote and conserve enset diversity through research, teaching and outreach. A similar initiative, from Dilla University, has focused on community outreach by creating a food festival, ‘enset on wheels’. These activities are resonating within local government offices, which are becoming increasingly aligned with farmers’ needs by propagating enset and other traditional crops in nurseries. An expanding enset nursery in the regional town of Chencha is one example.

Nationally, the Ethiopian Biodiversity Institute has collected more than 80,000 accessions of indigenous species, including crop varieties. These are valuable for global and local crop breeding efforts, as varieties that are resilient to changing climate, pest, and disease conditions may be used to develop more robust and productive crops. However, for these seeds to benefit Gamo farmers, crops must be appropriate to variable highland conditions and seasonally available for an affordable price.

There is no single pathway toward sustainable and productive agriculture in the Gamo Highlands. For these changing systems to reach a new balance, farmers and communities will need access to all available options – old and new – through local and regional markets, government extension, and new combinations of formal and farmer managed seed networks. Adapting to the changes facing Ethiopia requires diversity – of approaches, institutions, stakeholders, crops, and genes.

Dr. Leah Samberg (lsamberg@umn.edu) is a research associate with the Global Landscapes Initiative at the University of Minnesota’s Institute on the Environmen