In recent decades, resource challenged hill tribe farmers and gardeners in northern Thailand have recognised the importance of various threatened species that yield non-timber forest products.Conserving these species in agroforests has not only secured farmers’ access to valued types of food, fibre, and construction materials, but also improved fallows and the integration of displaced communities from Myanmar.

While chickens forage in the undergrowth, Jawa Jalo tends a productive forest-like garden at his home in northern Thailand. About 0.16 ha in size, he established the plot in 2003 on degraded land adjoining his home. It contains 27 different crop varieties, the majority being indigenous non-timber forest product (NTFP) species. The dense, multi-storey planting of trees, vines, and shrubs provide Jawa (a resident of the Red Lahu community of Huai Pong) with a constant supply of food and fibre, both for household consumption and the market.

The Red Lahu, Palaung, Akha, Lisu, and Karen are amongst many ethnic groups residing in the Sri Lanna National Park, in Chiang Mai province. Originally rooted in neighbouring Myanmar, many of these communities fled armed conflict more than three decades ago and sought refuge in Thailand. Migrant communities in Thailand are routinely marginalised by the local population and suffer limited and uncertain access to farmland.

Innovation born out of need

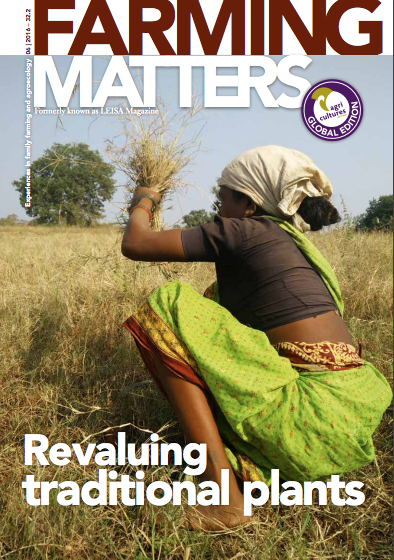

NTFP species are almost always included in home gardens. Photo: Rick Burnette

Before the establishment of the National Park in 1989, local farmers practiced shifting cultivation, with fallow cycles of up to nine years, growing mainly upland rice and other crops, such as sesame, chillies, cowpea and pigeon pea. Access to forests enables this traditional form of farming and helps to supplement household nutrition, as well as provide medicines, construction materials, and other products. However, environmental degradation and legal restrictions progressively weakened traditional forest-based livelihoods. With ever greater restrictions on shifting cultivation in northern Thailand, existing forest-fallow periods are increasingly brief, often only a few years. And households are now restricted to small plots of untitled land that was cleared decades ago.To cope with diminishing access to forest resources, other hill tribe communities outside of the Sri Lanna Park began family agroforestry plots for the production of NTFPs. For instance, while cultivating traditional field crops, some farmers have integrated forest species as another source of edibles in their fallowed fields. These NTFPs often include rattan (Calamus and Daemonorops spp.), valued for fibre and edible shoots, as well as prickly ash (Zanthoxylum rhetsa) which produces a marketable spice.

But indigenous NTFP species were not only integrated into fallowed fields, people also started to grow them in their home gardens. The migrant Palaung communities are among the most recent arrivals and face particularly limited access to farmland and forest products. As a result, many families began planting indigenous species around their homes. These included perennial vegetables such as snowflake tree (Trevesia palmata), rattan, cluster fig (Ficus racemosa), red shoot fig (Ficus virens), and climbing acacia (Acacia pennata).

Farmer-to-farmer learning

Access to forest resources helps supplement household nutrition

Inspired by these locally developed approaches, the Upland Holistic Development Project has been promoting community driven NTFP agroforestry in northern Thailand since 1999. The project supports farmer-tofarmer exchange where households already practicing some form of agroforestry offer models for other farmers to learn from. These households provide inspiration and offer assistance to newly established communities. For example, they provide planting materials, practical information and encouragement. Some of the farmers also host demonstration plots. As a result, the newcomer communities, which often settle in environmentally degraded areas, have begun to explore and experiment with indigenous forest species in their home gardens.

A fine line

NTFP species play a significant role in the regional economy. Photo: Rick Burnette

NTFPs are often managed and harvested at a subsistence level and are not usually considered to be important crops, particularly in comparison to major regional commodities such as rice and maize. But the hill tribe farmers in northern Thailand prove the opposite. NTFPs, which play a significant role in the regional economy and in household food and nutritional security, are often long-domesticated crops derived from the forests of the region – for example, longan (Dimocarpus longan), bael fruit (Aegle marmelos), and prickly ash. These domesticated species also help to preserve local cuisines and culture, while contributing to regional biodiversity and forest preservation. Almost always included in backyard home gardens, NTFPs are not only for household consumption, but sold in markets. These may include annual and perennial vegetables and fruits such as climbing acacia leaves, salae flower buds (Broussonetia kurzii), rattan shoots, ivy gourd shoots (Coccinia grandis), fronds of vegetable fern (Diplazium esculentum), spiny lasia leaves (Lasia spinosa), cassod tree leaves, bael fruit and Burmese grape (Baccaurea ramiflora).Moreover, NTFPs are often established on permanent upland fields among fruit trees, with density and variety needed to create a multi-storied structure. Larger trees form the canopy and smaller NTFP species grow in between or underneath the canopy and use the larger trees for support. In more remote locations where short-cultivation, long-fallow swidden cycles still exist, the opportunity to improve fallows with useful NTFP species – such as tea (Camellia sinensis), rattan, prickly ash, fan palm (Livistona sp.), black sugar palm (Arenga westerhoutii), and leguminous species such as the cassod tree (Senna siamea), lablab (Lablab purpureus), and rice bean (Vigna umbellata) – increases the value of the fallow by maximising and diversifying agroforestry production and improving soils.

NTFPs offer year-round production

Factors of success

Indigenous and naturalised forest species are valued for inclusion in agroforestry systems because they require few, if any, external inputs. Next to the Sri Lanna National Park, cultivation of NTFPs is successful where, for most communities, shifting cultivation is no longer an option. Depending on the diversity of plantings and the seasonal productivity of each crop, NTFPs are also able to offer year-round production, which gives them an advantage over annual crops. They are, moreover, products that are suited to local tastes and needs, some of which are readily marketable. Amongst these communities, cultivation of NTFPs has also been widely adopted thanks to the sustained support for farmer-to-farmer exchanges from local and international NGOs and civil society.

A growing forest

Although Jawo Jalo has not kept accurate records of establishment or maintenance costs of his garden, his income has increased substantially since 2008 from sales of NTFPs – primarily rattan and fishtail-palm shoots, as well as vegetables. Nearby farmers report increased income from NTFPs as well. One of these farmers is Mr. Namsaeng Loongmuang from Pang Daeng Nai, a nearby migrant community. He cultivates a 0.64 ha agroforestry plot similar to Mr. Jalo’s. He also promotes agroforestry, hosting an average of 10 groups per year with visitors coming from more than six countries.

In the meantime, approximately 190 families have established NTFPs in their home gardens, diversified permanent upland fields, or mixed orchards. Another 88 households have adopted and maintained backyard gardens with NTFP crops. NTFP-focused agroforestry is proving to be a viable option amongst migrant communities in northern Thailand struggling to sustain upland cultivation and access to land. At this rate, it can be expected that this option will continue to spread, in northern Thailand and to neighbouring countries where groups face similar landuse pressures.