Pastoralism provides a living for between 100 and 200 million households, from the Asian steppes to the Andes. But misguided policies are undermining its sustainability. Farming Matters looked at how governments can best strengthen the governance of pastoral systems and find more equitable ways to include pastoralists in policy making. Land tenure and joint management prove crucial to the answer.

IUCN, and Sue Cavanna, IIED

Pastoralism, the extensive production of livestock in rangelands, is carried out in climatically extreme environments, where other forms of food production are unviable. Providing a livelihood for between 100 and 200 million households, it is practiced from the Asian steppes to the Andes and from the mountainous regions of Western Europe to the African savannah. In total, its activities cover a quarter of the earth’s land surface. As well as generating food and incomes, these rangelands provide many vital, and valuable, ecosystem services such as water supply and carbon sequestration: services that are being degraded through misguided rangeland investments and policies.

Although some countries now officially recognise the value of pastoralism, negative perceptions still pervade. Pastoral policies are either non-existent or, where they do exist, are barely enforced. Establishing communal land tenure is crucial because it creates pastoral rights of access, provides opportunities for individuals to seek optimal ways of exploiting available resources, and facilitates changes in resource equity. However, the common property regime, which allows pastoralists to sustainably manage vast areas of land, is undermined by laws and policies that promote the individualisation of land tenure. As a result, dry-season grazing reserves have been lost, livestock mobility has been restricted, land tenure has been rendered insecure and land degradation has increased, undermining the sustainability of the pastoral livelihood system.

Securing land tenure in Garba Tula

Innovative solutions in Mongolia

Nomadic livestock producers form the backbone of Mongolia’s economy, where herding is a way of life. In recent years, grasslands in Mongolia have become overgrazed, affected by prolonged drought and poor management by the state. Mongolians recognised that innovative solutions were needed to tackle these issues and are trying out what is commonly known as the “comanagement approach”. This approach involves collaborative arrangements in which local resource users, such as herders, share responsibility and authority with governments for managing natural resources. The approach draws on the experience and expertise of all the players involved. Local users contribute their knowledge of the resource and past customary practices, while governments provide an enabling environment, including supportive policies and technical advice.

The co-management approach is being tested by a project team that has created two groups: community herder groups and district level comanagement teams that include community members, local government and civil society members. Together they have formulated agreements on how to manage grasslands and related resources. Local communities now have secure access to the resources they need and are developing institutions and methods to ensure they continue to have a voice. Co-management has resulted in productive pastureland, healthier herds, and increased incomes at the pilot sites. It is now being expanded into other areas and has led to legal and policy changes. Hopes are high for the future of Mongolia’s herders and grasslands. For more information, see www.idrc.ca.

This past decade, however, has seen a promising shift by several governments to recognise and regulate access and tenure rights over pastoral resources. Improvements have been made in Niger (1993), Mali (2001) and Burkina Faso (2002).

Mongolian government policy now supports communal land tenure through placing greater control of natural resources in the hands of customary institutions (see box). Benefits have impacted both pastoral livelihoods and the conservation of herders’ rangeland environments. Against this backdrop, it is important to identify and support processes that can help strengthen the governance of pastoral systems, as well as local land use and the environment. Pastoral societies also need to find more equitable ways of including pastoralists in the policy-making processes, as well as in the design of technologies and the makeup of the customary institutions that shape livestock production systems and environmental governance.

In Garba Tula, in northern Kenya, weak land tenure was identified as one of the key obstacles in the bid to improve the livelihoods of the region’s 40,000 predominantly Boran pastoralists. Garba Tula, an area extending over around 10,000 km2, has extraordinary biodiversity, but the full potential to conserve it was not being met, and people and their livelihoods were threatened by wildlife. In an initiative that emerged from meetings held by community elders in 2007 and 2008, a Community Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) approach was set up to strengthen tenure.

Spearheaded by a Community Task Force and strengthened by expert-facilitated consultations, the community arrived at a common understanding of CBNRM as “a way to bring local people together to protect, conserve and manage their land, water, animals and plants so that they can use these natural resources to improve their lives, the lives of their children and that of their grand children”. The strategy should improve the quality of people’s lives “economically, culturally and spiritually”.

Land in Garba Tula is held in trust by the County Council, but county councils generally exercise strict control over the allocation of land and are poorly accountable to local communities, who in turn are poorly informed of their rights. Contrary to popular perception, trust land is not government land, and it can provide a strong form of tenure if the community understands both its rights and the legal mechanisms to assert them. Garba Tula residents now document their customary laws and are encouraging the County Council to adopt them as by-laws. This will also provide a foundation for developing a range of investments that are compatible with pastoralism, such as mapping wildlife dispersal routes; residents are also interested in ecotourism.

The Community Task Force is setting up a local trust to manage the process and the painstaking procedure of ensuring community and local government buy-in is supported by a number of development, conservation and wildlife agencies as well as government. Since the vast majority of Kenya’s drylands are legally trust land, the Garba Tula experience could set a precedent for securing land tenure in other areas.

Encouraging community engagement

Policies and institutions must empower pastoralists to take part in policymaking that affects their livelihoods. This will also promote equitable access to resources, facilities and services, and guarantee sustainable land use and environmental management.

In addition to addressing issues related to livestock production, health and marketing, pastoral policies should also tackle critical issues such as healthcare, education, land rights and women’s rights as well as governance, ethnicity and religion. An important lesson from Garba Tula is that the policy environment may be more supportive than imagined, and what is missing might not be the policies so much as the capacity for taking advantage of them.

Published research on African pastoral systems has steadily overturned many of the misconceptions about pastoral systems, highlighting the importance of appropriate strategies to manage the variability of the climate in dryland environments. Effective management strategies will allow for diverse herds of variable size and keep them mobile.

There are increasing opportunities for pastoralists to capitalise on environmental services such as the maintenance of pasture diversity, vegetation cover and biodiversity through ecotourism or through Payments for Environmental Services. The Kenyan example shows that even in Africa, where competition over public funds is tough and such schemes are poorly supported, the situation can be changed through community empowerment and government accountability.

Text: Jonathan Davies and Guyo M. Roba

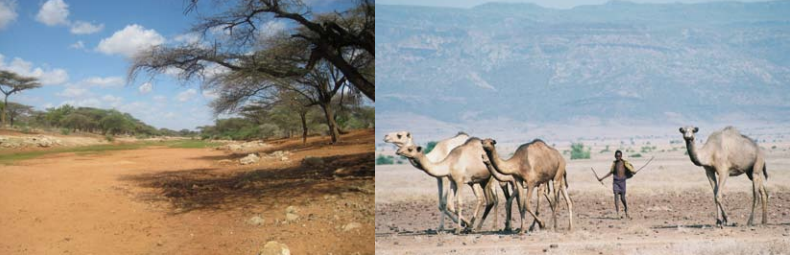

Photos: Pastoralism is frequently the best way to manage vast areas of land in a sustainable way. By: Jonathan Davies, IUCN, and Sue Cavanna, IIED

Innovative solutions in Mongolia photo: H.Ykhanbai