Communication is crucial in human interactions. The use of social media has become widespread, especially among young people. Modern communication tools can also be used to make agriculture more appealing and more effective.

Though neglected for a long time, Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) are now seen as an important tool for development, especially in Africa. There are many available options, and different factors need to be considered in selecting the most appropriate and effective tool or medium for communication.

According to Francois Laureys, the West Africa Programme Manager at the International Institute of Communication for Development (IICD), the most important factor is the type of information to be sent out: “In Africa, radio is still the cheapest and most efficient tool for spreading messages about a broad range of issues, like farming, democracy or lifestyle. By building in feedback-loops via the internet or telephone, it can also offer two-way communication.”

Using ICTs in farming, for example for spreading information about practices and market prices for agricultural products, requires other tools like mobile phones or computers. But in many parts of Africa, mobile phones are not (yet) widely used to support farming: most farmers who have mobile phones only use them as a social communication tool. Part of the problem is that there are still practical problems in the use of ICTs on a large scale: large areas of the continent are still not connected, and the communication costs are very high: an average person in Africa pays (relatively) ten times more for mobile communication than somebody in Europe. Practical ICT applications for farming are still limited. And illiteracy is still widespread, especially among the elder generation, which limits the full use of digital ICTs. But, according to Mr Laureys, there is a huge potential for using visual multimedia, such as video and photography, for training and learning about agriculture.

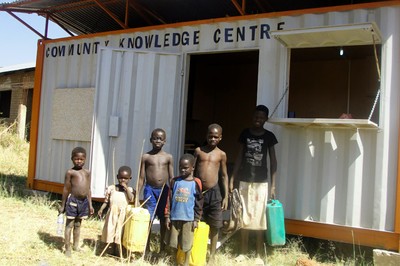

Container knowledge

ILEIA’s Kenyan partner in the AgriCultures Network, the Arid Lands Information Network (ALIN), has been promoting Maarifa centres (Kiswahili for “knowledge”) for the last five years. These are housed in recycled sea containers that have internet access and where the staff provides different services. They serve as valuable information hubs in remote areas, helping provide farmers and pastoralists with information on new agriculture and animal husbandry technologies, promoting their adoption and thereby improving the livelihoods of poor communities.

A typical Maarifa centre contains a small library of publications, CD ROMs, videos, DVDs, and five or more computers with broadband internet connectivity. Each Maarifa centre is managed by a field officer, a young woman or man with interest and training in information management of agriculture.

A young volunteer from the community, known as a Community Knowledge Facilitator (CKF), supports the field officer in running the centre. One key task is to ensure that everybody who visits the centre is well served, irrespective of their level of literacy. Although open to all villagers, the Maarifa centres make special efforts to engage the youth in learning about and using ICTs to search for agricultural information and for their broader communication needs.

The establishment of a Maarifa Centre is celebrated with an open day, bringing together the neighbouring communities, including representatives from the local government departments and civil organisations, community groups, schools, and the general public. An advisory committee, formed by the local community, co-ordinates the outreach activities around each centre, and each centre has a community focal group attached to it. This group will include some infomediaries with some expertise in extension. They are instrumental in supporting the field officers to package the information so that it is accessible to farmers. There are currently fourteen Maarifa centres; eight in Kenya, four in Uganda and two in Tanzania. Three of the centres in Uganda have only recently been opened, near the towns of Gulu and Moyo. In February 2011 one additional centre started near the Kenyan town of Elwak.

Information experts

John Njue is the field officer at the Maarifa Centre at Kyuso, a dry part of eastern Kenya, where the centre “acts as a referral point for people interested in developmental content. The district does not have any community library and therefore students of agribusiness, crop production and horticulture come to the centre for reference.” One of his tasks, after learning users’ information needs, “is to repackage the available information. In November 2010, for example, many farmers sought information on indigenous poultry keeping after weather anomalies related to La Niña were predicted. Many young people wanted to raise poultry as an alternative farming enterprise”. A year earlier, he helped many of the farmers who came to the centre looking for information on non-chemical pest management. Many women also come to the Maarifa centre: given the time constraints they face, many prefer to borrow i-Pods, with which they watch best practices carried out in other areas.

But John Njue is not directly involved in any agricultural enterprise. “I admire farming, but not the kind our forefathers practised. The reason why I don’t farm is because my parents and neighbours would not listen to my views about the need to practice more modern farming techniques, and trying to farm as a business.” According to him, most young people don’t engage in agriculture because of a lack of support from the people around them. He feels that it would be beneficial if the government employed young agricultural extension officers. This would make it easier to communicate to young farmers and help them start an agricultural business, rather than continuing to see and practice farming as a subsistence activity. He also observes that many extension officers do not use modern technologies in their training, and thinks that this is a deterrent to youth participation.

Samuel Nzioka is the newly appointed field officer at the Maarifa Centre in Nguruman, a very remote village in the south of Kenya’s Rift Valley Province. He has a BSc degree in agriculture and strongly believes that ICTs can help promote agricultural production: “ICTs can be used to document what the farmers are doing in one region. This information can be shared through CD ROMs, short videos and pictures.”He is also positive about Sokopepe, an application piloted by ALIN in order to “link farmers and agri-cultural commodities through an online mobile phone and an internet based marketing portal”. A youth group in Nguruman was trained in the use of ICTs and have developed their own blog through which they’re able to share what they are doing.

ICTs for organisation

ICT heroes, busy internet women

Estelle Akofio-Sowah is Google’s country manager in Ghana. She attended the “Fill the Gap” conference organised by Hivos and IICD in Amsterdam in January, where she said that smart phones will soon be the main source of internet access in Africa.

Mobile phones are already very significant communication tools, and prices for third generation digital technology are expected to drop significantly. But online content still needs to be developed. So there is much work for African web developers in making online services relevant to the local context and language.

Internet offers many opportunities for women, she says, especially for those who overcome their fears about technology and who dare to use their “natural flair” in this male-dominated sector. She highlighted the work of two heroines of the African digital world, Esi Cleland and Florence Toffa, whose work is helping AFROCHIC and the Word Wide Web Foundation reach their objectives.

Samuel Nzioka thinks that there are a number of ways in which agriculture could be made far more appealing to young people: by giving them grants to help them start farming; by linking them with markets for agricultural produce; by setting up local processing plants for value-addition and employment; by training them on best farming practices to achieve higher yields and by organising exchange-visits to learn from others. ICTs can be useful in all these cases.

Francois Laureys has seen the effects in Mali, where IICD supported a women’s association for producing and marketing shea butter. Three computers, some solar panels, two photo-cameras and one video-camera permitted the women to present their products on a website. The use of computers, coupled with management and marketing tools, helped raise production levels and improved sales and revenues. The women also managed to strengthen their organisation, with better accountancy procedures and reports.

But Mr Laureys also warns against too much optimism: “Having a website and being provided with market information is not enough to help the individual farmer get out of the poverty trap. A certain level of organisation is needed.” That’s why better results are seen when working with farmers’ associations and interest groups. The shea butter womens’ organisation has shown many positive results in Mali, and the Maarifa centres are playing an important role in strengthening and connecting rural organisations in remote areas of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. More than other villagers, young people are contributing to this.

Text: Anthony Mugo and Mireille Vermeulen

Anthony Mugo works as Programme Manager at the Arid Lands Information Network (ALIN). Mireille Vermeulen is part of the Farming Matters editorial team.