In April 2010, IFAD and FAO launched a joint programme to provide people working on poverty reduction projects, with the skills and tools required to gather and share knowledge gleaned from their projects. Different workshops in knowledge sharing techniques, writing effectively for different audiences, and systematisation were held in 2011. The last meeting was a “training of trainers” session, which specifically aimed to upscale the whole process. Participants of this workshop are now running their own knowledge management processes back home, training their colleagues.

People working on these projects acquire valuable knowledge and a wealth of practical experience. However, their knowledge is often “lost” when projects end.

By developing capacities to share knowledge, the FAO-IFAD programme helped ensure that projects build on proven successes and avoid repeating errors, that the voices of a wide group of stakeholders are included, and that knowledge is properly documented and well communicated, so that it can have the greatest impact.

Working with regional organisations (such as, for example, ICIMOD in Nepal), the programme offered “hands-on workshops” focusing on participatory techniques and tools for knowledge sharing, and on writing skills. In total, more than 380 people participated throughout the year, representing projects being implemented in countries as diverse as China and the Maldives, Sri Lanka and Vietnam.

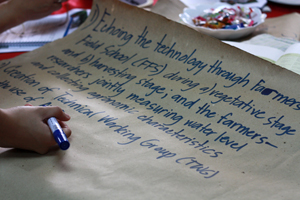

Focusing on “a methodology which facilitates the ongoing description and analysis of the processes and results of a development project”, the programme paid specific attention to a systematisation process. This meant presenting some basic principles (such as involving as many stakeholders as possible, or identifying the general conditions needed), and then actually starting a systematisation process for sharing knowledge. The work of some of the participants, such as Abdul Qayyum Abbasi, describing and analysing the Community Development Programme in Pakistan, has already been published and shared.

One of the most interesting lessons learnt was about the use of videos. Participants discussed the challenges that practitioners face in using images in a systematisation process. This doesn’t necessarily need expensive tools and materials – hand held devices such as mobile phones can be adequate. Videos are not only useful as a way of presenting a final product: they can also be used for collecting information (e.g. in interviews), for highlighting someone’s opinion, and for asking feedback from other participants.

Training future trainers

The programme also organised a three-day “training of trainers” session, with the objective of scaling up and sustaining the process. Some project staff who had attended the previous training events were invited to a workshop in Kathmandu, Nepal, in December 2011. The main objective was to present and discuss the issues that trainers (or facilitators) should consider when organising a systematisation process. Our discussions started by focusing on the necessary logistics and the general objectives. Participants discussed the advantages that such a process can bring in terms of advocacy, or simply by helping to “avoid re-inventing the wheel.”

We looked at the importance of carefully selecting participants, in a way so that they contribute to and benefit from the process as much as possible. Beyond considering different groups or stakeholders, and considering specific criteria (such as being associated to an IFAD project), we also looked at other regularly occurring issues: the difficulties of inviting and managing a large group, and thus the need to to select those who represent a large community, and the difficulties when having different “categories” working together (politicians with farmers, extension agents with the director of an organisation) which can lead to some participating much less than others. The discussions paid special attention to the role of the trainer, who plays an influential role in every systematisation process. Trainers need to decide their level of engagement: will they just provide the necessary resources for a process to take place, will they try to “catalyse” it, or will they actually take charge of it all? Each of these choices has implications for the selection of participants, and may mean providing mentoring, apprenticeship or coaching possibilities. Trainers also need to think about the different tools or techniques they will utilise and what, if any, incentives to provide to participants.

Finally, the participants looked at the steps that are common to all documentation processes, regardless of the methodology followed, and at ways of addressing the most common problems:

- How to select the “case” to be documented, which requires considering the audience who will benefit from the documentation process.

- How to collect data and information, and the importance of finding what information is already available, or of going to the field, and asking participants and stakeholders in situ.

- The need to encourage participation and involvement: (i) before the workshop, by selecting the “right” participants, (ii) during the workshop, by using different tools, defining people’s roles and responsibilities and defining and explicitly mentioning all expectations, and (iii) after the workshop, providing incentives, or inviting participants to contribute to any subsequent publication.

- The dissemination of the results, which starts by identifying the target audience and then deciding what type of document is best (a policy brief, an article in a journal, etc.). Such documents can always be reinforced and made more accessible by using different media tools, such as press releases, the internet, street theatre, posters, or radio programmes.

The last step involved a short discussion about the need of scaling up and sustaining these efforts and also every systematisation process. This meant looking at the necessary requisites (support, resources), and at the steps to follow. Jun Virola, from the Philippines, highlighted that “this workshop was a systematisation process in itself. We looked at where we are, what we have been doing, and we described what we want to happen. At the end we were able to prepare and share our action plans.” The first steps have been taken: many trainers are up and ready to start training their colleagues.

Text: Denise Melvin and Jorge Chavez-Tafur

Denise Melvin, Communications Officer at FAO, worked as Programme Coordinator on the FAO-IFAD Programme for the Development of Knowledge Sharing Skills (e-mail: ks-asia@fao.org).

Jorge Chavez-Tafur facilitated the training workshops in the Philippines, Nepal and China.