Farmer organisations can be both effective and efficient in training their own members. Their work, however, also reminds us that agricultural training is not just a technical field. Their commitment to agro-ecology shows that, above all, training is a political issue – and they’re challenging us to follow them.

Since the 1990s, the closure of many public extension services in the Sahel has had a severe i

Today, producers are facing profound changes – economic, geo-climatic and institutional – which require adaptations and new skills, especially in the current context of chronic food insecurity.

Farmer organisations (FOs) bring together the producers in a region, and thus group and represent the end users of every training process. Faced with the challenges mentioned above, it seems logical to conclude that they are better able to de!ne and articulate the training needs of farmers in a given area, according to the needs of the market, but also according to the social, cultural and technical features of a region.

Even better, FOs are not just simple intermediaries that can identify and select the target group. In most cases they are able to provide training courses themselves, since they know the problems farmers face, and the potential solutions, better than anybody else. The costs of training and of providing extension services can also be lowered if it is carried out by farmer organisations themselves. This can be a very positive factor for scaling up and reaching a large number of producers.

In practice, however, the training courses organised and conducted by FOs are not always systematic or comprehensive, and may depend on existing opportunities, which can be quite often linked to the presence of projects. And it’s true that the quality of trainings varies greatly: the trainers are not always prepared, leaders not always fully involved, cost control is not a major concern, and there is frequently no post-training assessment. Sometimes the role of FOs can be limited to identifying the target groups and selecting participants, without having neither the ownership nor the responsibility for training.

This lack of ownership is part of a long-term pattern. Historically, many FOs in West Africa were created in order to represent the farmers in a region and bring the voices of producers into the legislative frameworks and the elaboration of national policies. But they were not intended to provide services to their members. The SahelAgroFormation project (SAF) wanted to work with them in a different way, and support those organisations wishing to train their members on their own.

This is the main objective of our work with the Coordination of Peasant Organisations of Mali (CNOP, in French), the Peasants’ Platform of Niger, and also organisations such as the Regional Union of Agricultural Cooperatives of Kayes (URCAK) in Mali. In both Mali and Niger, SAF’s aim has been to establish sustainable training mechanisms, and not just to train beneficiaries.

A mutual learning process

The history of rural West Africa is tainted by the presence and excessive power of outsiders: colonists, urban elites, state representatives, etc. These outsiders represented the interests of what are known as the “economic growth sectors”, such as cotton or peanuts, and to some extent they still do.

Focusing on commercialising these products, they offer technological packages that include incentives such as access to credit or specific inputs. Many training programmes are then built around these packages, relying on incentives or subsidising the training courses, or even remunerating participants for attending. Farmers have little choice.

We too started by identifying the “growth sectors” for which training is needed. However, we were especially interested in the local demand. In economics, the term “demand” refers to the needs and wishes of consumers or recipients. Thus, instead of planning and implementing a training process which focused only on those crops or techniques which are part of the “growth sectors”, our project focused on what the farmers were demanding. In so doing, we were surprised by the concerns of our partners. What interested them primarily was political legitimacy – or ownership – of the training process, and especially of the subjects taught.

Our work with farmer organisations in West Africa taught us that agricultural and rural training in the region needs a different approach, as it is largely and inevitably a political issue. It is different from (say) repairing a motorcycle engine, which does not force us to opt for a speci!c development model, as the skills and components required do not fundamentally change from one place to another. Agriculture is not the same. A detailed study in the Sahel put it clearly: “One of the main lessons learned was that there are no technically perfect solutions, but that all solutions are political. Therefore aid agencies have no legitimacy to offer” (Loic Barbedette, 2002).

Without abandoning the required economic focus, we at SAF decided to support the political aims of our partners, gaining credibility and their trust. This choice greatly strengthened our position and ability to carry out our activities – to the point of being able to conduct trainings without external funding.

From the local context to agro-ecology

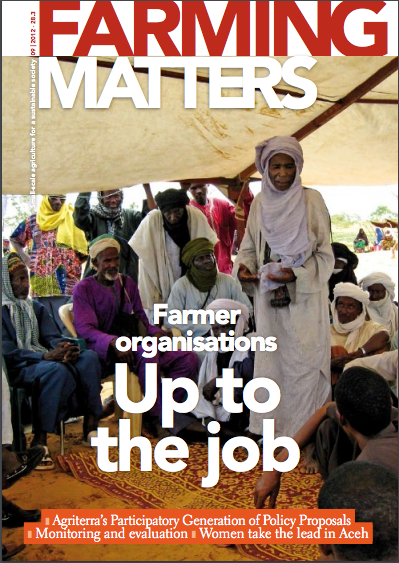

sovereignty. Photo: Yves Matthijs

When our project started, one of our objectives was to see training as one of the possible responses to some of the numerous and complex issues faced in the Sahel. This meant analysing the context and overall setting, and not limiting ourselves to the local opportunities for commercialisation.

But which context(s) to focus on? We had a clear point of view. So did the leaders of different organisations. And, what about the farmers and producers who were to be the users of the service? We had to ask ourselves what type of farming to focus on.

Working with farmers and their organisations, we saw that the definition of the context is the first political act of any action; that there is nothing less objective than de!ning the context. This starting point leads to a series of strategies, actions and outcomes. While projects frequently focus on markets and commercialisation (access, diversity, inclusion), farmers prioritise production factors (soil, water, land), and organisation leaders focus on issues such as ownership, sovereignty, and empowerment.

Most producers wanted us to initially tackle what they see as their fundamental problems, starting with the fertility of their soils and the access to land and water. Is it appropriate to explore ways to market a specific product, or to grow a new seed, if the farmer does not even have control over these key elements of production?

Not surprisingly, an agro-ecological approach emerged as the central element of the agricultural training offer. The reasons seemed obvious to all those we were working with: agro-ecology helps restore the soil, while offering good positive returns (especially in the Sahel). It can be easily understood and appropriated by farmers (some of whom have been practicing agroforestry for several centuries), and, most of all, it is economically viable. For producers, agro-ecology is a culturally and economically attractive technical solution to their concerns. It also provides much-needed resilience. For farmer organisations, agro-ecology is part of the process towards food sovereignty.

To be continued…

After only a few years, we have more than 40 training modules in agro-ecology, all of which have been developed or adapted with local producers and their organisations. Up to 65 local techniques have been identified in Niger (including 17 agro-ecological techniques that are not taught in agricultural schools) as part of our efforts in valorising and disseminating endogenous knowledge. All of these are being shared with producers through the trainings. As a whole, this is the first formal and more or less complete training package that is truly adapted to the region.

A network of local trainers, or “peasant relays”, is being set up in Mali and Niger, operating with the maximum possible level of self-financing. In the same way, agricultural advisory services by farmers’ organisations are being developed in Mali and Niger, with the objective of expanding and standardising the basic training systems, and having more influence on national policies, donors and other projects. As one of the representatives of the Horticultural Network of Kayes (RHK in French) put it, “This is the future. We need to create this pool of trainers and ensure the stability of the training process. This gives us the chance to save money, reinforces our internal cohesion, and lets us focus on what we want“.

In addition to these results, and to the important task of expanding them further in the coming years, the most important lesson has been that farmer organisations have shown to those who boast years and years of training experience in West Africa: that training is never neutral. Training inevitably conveys doctrines and ideologies, and thus preferences. It is above all politics – especially in agriculture. NGOs must focus more on supporting the projects and visions of their partners, rather than pushing them to follow our perceptions of what development is. Through learning from producers and their organisations we can develop ourselves and learn to better do our job.

Yves Matthijs

Yves Matthijs (coordin_saf@live.fr) works as project manager for SahelAgroFormation. This is a project implemented by Swisscontact and funded by a European Union grant, which has the objective of developing “agricultural and rural training services based on demand”.

More information can be found at http://swisscontactniger.org/04_0SAF.htm