(september 2012) Farmer organisations represent the social capital needed in the rural areas, says Thomas Mupetesi. National policy makers should pay attention to the role that farmers’ organisations can play in tackling environmental issues, building on what organisations like ours are doing. What we need to do is to share the lessons learnt and show what these organisations are already doing to respond to climate change.

Recurring droughts have contributed to the increasing levels of poverty seen in Zimbabwe over the past 20 years. Viable solutions to address this problem remain elusive, and drought, as a result of climate change, is expected to have an even greater effect in the near future.

There is growing evidence, however, that social capital, as “the collective value of all social networks”, can help farmers adapt to environmental change, and also to adopt a more environment-friendly attitude.

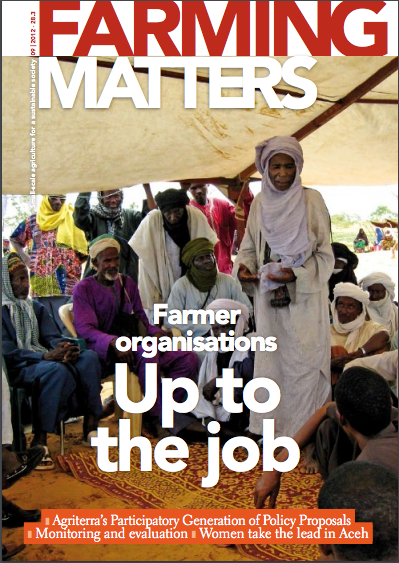

Farmer organisations represent the crucial social capital needed for transforming the agricultural sector in Africa. As platforms for collective action, these organisations can have a very positive effect by improving their members’ economic and social situations.

Farmer organisations in Zimbabwe, for example, help farmers market their products, resulting in higher incomes. But detailed studies have also shown that membership is directly linked to participation in local community events, and thus to the creation of social capital. Membership of a farmer organisation helps farmers learn new ideas and techniques for ecologically sound farming and for conserving an area’s natural resources. Organisations can therefore play a pivotal role in improving a region’s environment.

A small but growing body of literature links social capital to a healthier environment, but less has been said about its role in building resilience. Yet experience has shown that membership of a farmer organisation helps individuals enter into reciprocity arrangements with friends, relatives, neighbours and local institutions – as we have seen within FACHIG. These exchanges shape individual actions.

Countless analyses have shown that, where social networks are present, households are better able to prepare and plant their land on time, or have a wider stock of seeds to rely on, and are thus less prone to risks. Reciprocity is crucial in poor and isolated communities, and plays an even more important role in these communities’ responses to unexpected situations.

Another important aspect here is what the literature refers to as “linking social capital”: organisations provide links to a region’s authorities, helping farmers leverage resources and increasing their bargaining power.

National policy makers should pay attention to the role that farmers’ organisations can play in tackling environmental issues, building on what organisations like ours are doing. What we need to do is to share the lessons learnt and show what the farmers’ organisations in Zimbabwe and elsewhere are already doing to respond to climate change. These experiences can then be translated into sound policies to support farmers’ efforts.

Thomas Mupetesi

Thomas Mupetesi is the Executive Director of the Farmers Association of Community Self-Help Investment Groups (FACHIG) in Bindura, Zimbabwe. He is also a member of the Agrobiodiversity@knowledged community.

E-mail: mupetesi@yahoo.co.uk