Water is generally taken from different sources, and used for multiple purposes. The multiple-use water services approach, MUS, contrasts sharply with the sectoral divides that are common within the water sector, which view domestic use, irrigation and sanitation in isolation rather than as a whole. Pilot projects in different parts of the world show the many advantages of integrating multiple uses and priorities.

In the informal water management system seen in most communities, water is typically taken from multiple sources, and infrastructure is developed for different uses. Integrating the use and management of these water sources for integrated livelihoods brings lifesaving resilience.

In a sense, water users worldwide have always negotiated, silently but successfully, with public-sector planners and engineers: they often make multiple use of water schemes designed for a single use, whether in a “legal” way or not. However, such strategies can cause problems if they are not planned for.

Cattle may damage irrigation canals; getting water for gardening from a communal piped system designed to provide small quantities of drinking water, may deprive downstream users or other community members. Planners, in government programmes and NGOs, can solve these problems and respond to these silent negotiations by planning public water schemes for multiple uses, according to people’s priorities.

Multiple-use water services

In recent years, this new water services approach has been piloted and disseminated as “multiple-use water services” or MUS. An international core group of 13 partner organisations (the International Water and Sanitation Centre, International Water Management Institute, Winrock International, Rain Foundation, ODI, Pump Aid, IFAD, FAO, Challenge Program on Water and Food, World Fish, Cinara Colombia, WEDC, and Plan International), together with 300 other members, have been bringing experiences together from their various pilot projects, identifying lessons and exchanging ideas.

Projects always begin with participatory planning at the community level, which is used to identify the main priorities of all users, including women and other marginal groups. This helps projects come up with technical designs that accommodate all uses and anticipates, and as much as possible avoids, possible conflicts between users. The participatory planning process is also used to establish rules and enforcement procedures.

MUS is good news. By installing water infrastructure or technology, it focuses on providing a “service”, offering water resources to people – in the right quantity and quality, at the right site and at the right time. But, unlike conventional public investments in single-use water infrastructure, it makes additional investments in water supply systems, reservoirs or irrigation schemes which generate many more benefits.

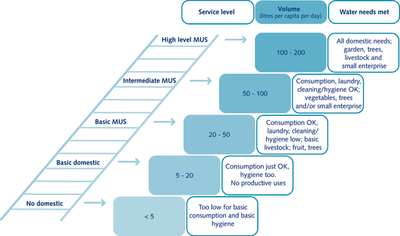

Building on people’s own needs and practices increases the likelihood that the systems will be more sustainable. Water provision for domestic and productive uses at homesteads ensures that users can “climb the multiple-use water ladder”, moving from using 25 litres per person per day to between 50 to 100 litres per day (see figure on page 34). While people may only need between 3 and 5 litres of water per day for drinking and cooking, moving up the ladder allows households to meet their other domestic needs, rear livestock, irrigate their fields, or even start a small enterprise.

At a community scale, MUS considers all water users, uses and sources: rainfall, surface streams, ponds, lakes, wetlands, and groundwater, in a holistic manner within the spatial layout of a community’s land and waterscapes. The planning and design of water infrastructure for multiple uses is facilitated in a participatory and integrated way by water service providers from the local government, line agencies, NGOs, or by community mobilisers themselves.

MUS takes an integrated approach to water development and management, integrating domestic, irrigation and other uses. Potential conflicts arising from competing claims for different uses are anticipated and addressed, paying special attention to the needs of the marginalised.

Experience shows that, almost anywhere, the available water resources are sufficient to ensure that everyone can have access to between 100 and 200 litres per person per day – if the infrastructure is available.

Pilot cases in southern Africa

Several community-scale MUS pilot projects have been implemented by the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC), supported by the Danish International Development Agency (DANIDA). Between 2004 and 2009, SADC/ DANIDA tried out this approach in seven communities in Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland and Zambia.

A participatory process helped communities make their own spatial assessments of all the existing water resources, water technologies, their uses and users, as well as of the existing institutional arrangements. The main problems in each community were identified, and a long-term vision was formulated that took into consideration how the community wished to develop and manage its water resources. This generated a number of options for short-term intervention.

Representatives from each group in the community, women and men, the poor, crop cultivators and cattle owners, irrigators and farmers of rainfed land, members of the traditional chiefs’ clans, and elected political party members in local government, negotiated a ranking of all these priorities. Activities were then selected within the available budget and time frame. After developing concrete action plans, with price tags, the budget allocation was finalised and transparently spent as the action plans were implemented.

The seven communities prioritised a wide range of interventions: in Ndonga, in Mozambique, villages chose to have new boreholes with hand pumps for multiple uses. Villagers in Namwala, Zambia, opted for the rehabilitation of a dyke in a flood plain, while in Maplotini, in Swaziland, they planned a communal garden and irrigated sugar cane.

The list of priorities also included rehabilitating existing boreholes and wells, constructing and rehabilitating dams for cattle and other uses, upgrading village reservoirs, building a new weir in a hill stream, improved toilets, piped water supplies to homesteads for multiple uses, electric boreholes for both domestic uses and gardening, a communal solar pump and individual petrol-driven pumps for field irrigation, or even the eradication and commercialisation of invasive tree species.

A key lesson was the importance of involving the marginalised from the outset. For example, women give more priority to water for domestic and other uses than men. By planning together, women can convince the men of the importance of this. Without an understanding of the local hierarchies and without reaching out to include representatives of the marginalised groups in the planning process, the process is always vulnerable to being captured by an elite who favours technologies that suit them best, and look for a way of getting the “communal” technology sited near to their properties. If this happens the participatory community-based approach will hide, and legitimise, the elite’s appropriation of project resources meant for everybody.

Similarly, there is a strong need for transparency about budgets and how they are spent – especially as there are no standard procedures for checking this. Special implementation agencies were recruited for these pilot projects, but in general it is better to integrate such projects with the local planning processes, run by local governments. The integrated water development process then becomes part and parcel of the re-iterative local development plans.

Hybrid systems in Nepal

Springs and mountainous streams provided water year-round, but the flows were low in the dry season. From 2004 onwards, 70 gravity surface water schemes were implemented. These were designed for both domestic and productive uses around homestead land, according to the communities’ (and especially women’s) priorities.

The communities’ suggestions on how to effectively use multiple sources strongly influenced the technical design. For example, in the water-scarce village of Karre Khola (in the western district of Surkhet) traditional irrigation canals to more distant plots were lined to reduce seepage.

The water saved was diverted to a newly constructed storage tank connected to multiple use tap stands. But despite these improvements, the water rotations took too long during the dry season and were unreliable.

People’s water needs also differed, according to the crops they were growing. As a result, and in spite of the high costs, people opted for household storage jars for productive and domestic uses in the dry season. An already existing domestic water system, with a very limited capacity, was reserved solely for drinking water. After some time, the community extended the MUS system by channelling additional water from another spring. They continue to plan and lobby to develop additional sources of water to meet their multiple needs.

The key role of local government

A key finding in both examples has been the pivotal role that local government plays in facilitating and delivering integrated multiple-use water services. There are many reasons for this: it has a permanent presence; it knows local needs; it maintains a good relationship with community leaders (and can therefore mobilise contributions in cash and kind); mediates for conflict resolution; and is, in principle, able to call upon technical expertise where needed (for issues such as dam safety).

Local governments can also coordinate the allocation of donor and government funds; share expensive construction equipment, and can monitor the maintenance and repair of infrastructure. Empowering local governments, while ensuring accountability to local communities is, therefore, a key aspect of MUS and is one that is in line with the global move to encourage decentralisation, which increasingly devolves responsibility and resources to local governments.

Text: Barbara van Koppen

Barbara van Koppen (b.vankoppen@cgiar.org) is Principal researcher at the Southern Africa Regional Program, International Water Management Institute, Pretoria, South Africa.