Kaluchi Thakarwadi is a small, remote settlement in the district of Ahmednagar, in Maharashtra, in the semi-arid zone in the rain shadow of India’s western mountains. Rainfall is unreliable, so there is chronic water scarcity, with recurring shortages of food and fodder. Six years ago a broad watershed management programme was established, which has already had an enormous impact: a transformation from desert to a replenished watershed.

Villagers in Kaluchi Thakarwadi depend on agriculture, but only 2 of the 7 hamlets are close enough to the river to be able to use its water for drinking and irrigation. Many of them had to migrate temporally or permanently in search of work in the cities, or as labourers in large plantations.

The community lacked the resources or the collective power to tackle the problem of water scarcity and land degradation, and neither government officials nor development schemes had reached this village a few years ago. It didn’t even have a road leading to it until 2009.

Then, reports of the impacts of different watershed projects came in from neighbouring villages, and the people of Kaluchi Thakarwadi decided to try a similar approach in their village. In 2005, the local authorities contacted Shree Hanuman Watershed Vikas Sanstha (SHWVAS), a small NGO working in the area, who in turn contacted the Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR).

A few conditions

A national-level effort

Many different Watershed Development Programmes have been implemented in India during the past 40 years. These include those implemented by Ministry of Agriculture; the Drought Prone Areas Programme, Desert Development Programme, Integrated Wastelands Development Programme (implemented by the Ministry of Rural Development since late 1980s), and also the National Afforestation and Eco-Development Project, implemented by the Ministry for the Environment and Forestry, since 1989. Focusing on the adoption of appropriate production and conservation techniques, these have been successful in their aim to increase the production potential of the dry and semi arid regions of the country. Following a holistic approach, these programmes have helped regenerate wastelands, increase the fertility of the soils, lower erosion levels and contribute to the conservation and better use of the water available.

A number of projects supported by bilateral donors and international funding agencies have been launched since the 1980s. In the Indian context, the importance of these efforts lies less in their overall financial contribution than in their flexibility to experiment with and “pilot” new approaches – a flexibility which government norms and procedures do not easily permit. One of the many cases has been the Indo-Swiss Project on Watershed Development (2003-2004), implemented by the Karnataka Watershed Development Society. Working as a strategic partner, the AME Foundation focused on participatory learning processes like Farmer Field Schools and on the improvement of farm productivity “between the bunds”. Many other NGOs have also promoted similar efforts in different parts of country. Projects like Sukho Manjari (on the Himalayan Foot Hills), Haryana or Ralegaon Sidhi, to name just a few, received a lot of attention because they significantly increased the availability of water. These projects paved the way for the formulation of the National Watershed Development Project for Rainfed Area (NWDPRA), which was launched in 1990, and is now being implemented in 28 states. (T.M. Radha)

WOTR’s programmes are designed around the belief that the success of any project depends on the motivation of the community, and on its willingness to take ownership and participate in it. We see a watershed development programme not only as an effective way for fighting desertification, but also as a means for community development and building socio-economic solidarity. But there are certain pre-requisites for a programme like this one to work in any village:

The first is voluntary shramdaan, or the labour contribution from every family. As elsewhere, it was initially difficult to convince the people in Kaluchi Thakarwadi of this. Their financial condition being critical, it was natural for them to think only in terms of their own household and in terms of immediate incomes.

In addition, the high levels of migration had created a scattered, disjointed community, and efforts were needed to get them to think of themselves as one cohesive unit. So we opted for a strategy that has worked in other places of extreme financial crisis, combining shramdaan with paid labour in order to ensure that the people’s daily needs are fulfilled.

A second pre-requisite is the involvement of all the groups within a community. The villagers here live in remote, dispersed hamlets, and do not have much access to information. The villagers did not easily accept our condition that people from all parts of the village, regardless of their status or gender, would come together and participate in the entire process, especially in the planning and monitoring activities. This meant breaking years of socio-economic barriers. Initially, the women did not come to meetings at all.

A number of meetings between the organisation and the villagers were needed to gain their trust. Slowly, a few people were convinced of the importance of the programme and helped us convince all the others to join. Bit by bit, women started attending all meetings and getting actively involved in the programme.

The third condition we had to agree to was that of Kurhad-bandi (a complete ban on tree felling) and Charai-bandi (a ban on open grazing in treated areas). Villagers realised that our joint efforts could only work if trees were protected from the axe and from livestock.

Different activities

The programme started as soon as there was consensus around these pre-requisites. Work began in January 2006, and during these six years it has considered a set of different actions, ranging from the installation of hand pumps to microfinance. Throughout the years, however, it has focused on three main areas:

(a) Soil and water conservation.

Watershed “treatments” are important in containing desertification and replenishing degraded lands. Through various different efforts, depending on the lay of the land, running water is made to walk. Slowed down water percolates into the ground, increasing the soil moisture and also raising the groundwater levels. The problem of fertile topsoil being washed away by flowing water is tackled in this way. The treatments used in Kaluchi Thakarwadi were similar to those used in other semi-arid regions where WOTR has worked, and included continuous contour trenches, farm bunds, and also a check dam.

(b) Capacity building.

Together with the technical efforts, which were implemented at the farm level, we thought it important to make everyone aware of what a watershed development approach means, and the implications it has. We organised a series of training courses and held meetings with different sections of the village and, based on the principle of “seeing is believing”, arranged exchange visits to other districts in the region so farmers could see the positive results achieved elsewhere. This was often a key factor in convincing them to join.

(c) Institution building.

Community based organisations (CBOs) are a crucial link between the people and the supporting organisations, and in our projects they are responsible for every aspect of the project. A 15-member Village Development Committee (VDC) was formed, with members representing all the hamlets, the different wealth classes (including the landless), and with equal representation of men and women. Since 2006, the VDC has met regularly to plan, implement and monitor all project activities, and manage the project’s finances, with WOTR staff playing only a supervisory role. We also worked with women’s Self- Help Groups (SHGs). Forming a SHG is not an easy task in a remote, tribal hamlet like Kaluchi Thakarwadi. Three SHGs have now been operative for several years. They organise a savings programme for women and have also started producing and selling compost, and building and distributing energy-saving stoves.

Broad results

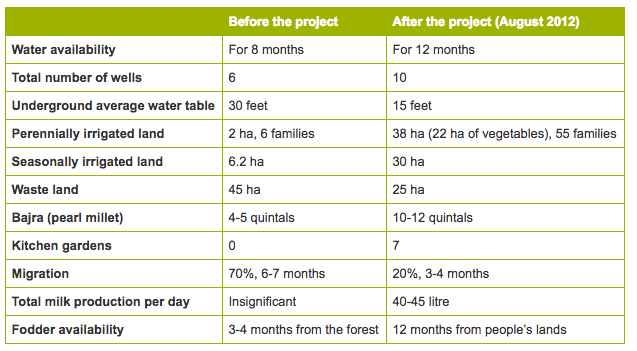

Farmers have benefitted greatly from their own conservation efforts. Although erosion levels have not been measured in detail, crop yields show a substantial increase (see table). And the wells that barely filled up in the rainy season now have water throughout the year. This means a second annual crop is now possible. In addition, the check dam has become a permanent source of drinking and irrigation water.

The most evident result of this programme is seen in terms of agricultural production and livestock. But WOTR’s Watershed Development Project is designed to rejuvenate much more than a land on the verge of turning into a desert. The cumulative result of this work is also obvious: greater economic prosperity. People can now invest in their homes, their children and their lifestyles.

The first television and telephone in Kaluchi Thakarwadi appeared after this project. And the project has empowered the community: the VDC is now strong enough to directly approach the authorities and request access to what is rightly theirs. With the help of WOTR, they have even availed themselves of Caste Certificates which give them access to various schemes applicable to tribal populations. The VDC ensured that these government subsidies reached the village and have installed 15 drip and sprinkler irrigation sets. One of the hamlets has even got electricity as a result of consistent efforts by the VDC.

Rejuvenated lives

This is a story of transformation; of how the people of Kaluchi Thakarwadi changed their destiny and their environment from a desert to a replenished watershed. Kaluchi Thakarwadi is no longer a tragedy of inhospitable climate and uncontrollable circumstances. Through rejuvenating their landscape the villagers have rejuvenated their lives.

Watershed Organisation Trust

Watershed Organisation Trust (WOTR) is a not-for-profit NGO founded in 1993 that operates in the states of Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Jharkhand. 2nd Floor The Forum S.No. 63/2B Padmawati Corner, Pune Satara Road, Parvati, Pune 411009, India.

E-mail: info@wotr.org